Mohammad Tanvir Hossain –

The Israel-Palestine conflict is one of the most complicated and divisive issues in the world today, which started as a regional conflict one hundred years ago. a struggle for the same territory between two quite dissimilar parties. It has national, political, geographical, cultural, and religious roots. Israelis and Palestinians both want the same thing: land. To better understand its reasons and underlying issues, let’s retrace the Israeli-Palestinian conflict through a historical journey.

Roman Empire (70-300): The Diaspora

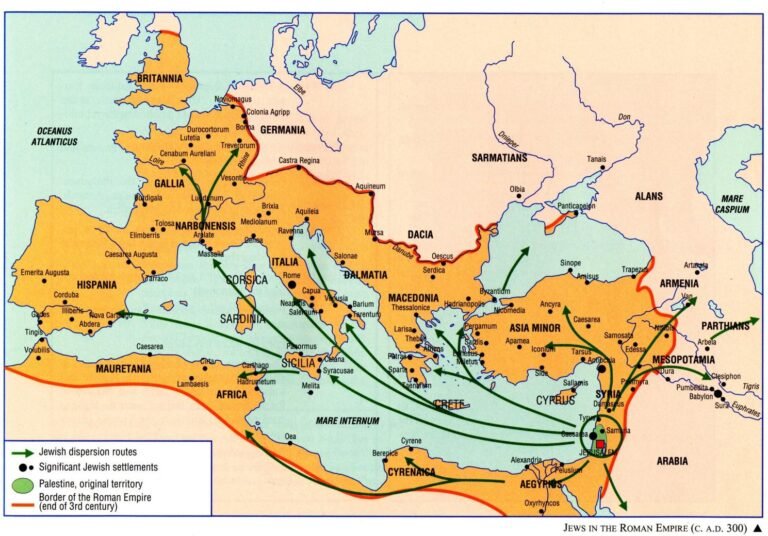

After the destruction of Jerusalem’s Second Temple in 70, a large number of Jewish people were exterminated and banished by Roman forces. 25 percent of the Jewish population in Judea, which is the region close to modern-day Israel, was wiped out, and 10 percent was reduced to slavery. Jews became a minority in their own country.

The majority of Jews fled to the Mediterranean region, which is today known as southeast Spain, southern France, southern Italy, Greece, Cyprus, and Turkey. Many Jews escaped to Mesopotamia, which is modern-day Iraq. Later, the Jews started to migrate north, toward what is now northern France, Belgium, Holland, Germany, Austria, Bulgaria, Bosnia, and Northern Africa (Egypt, Libya, Tunisia, Algeria, Morocco).

About 3 million Jews had relocated to the majority of the Roman Empire by 300, except Britain. 1 million people resided west of Macedonia (Greece), the majority in Asia Minor and to the east to the Caspian Sea and the Persian Gulf. Jews were present as far north as Cologne, Germany.

The Dark Ages (300-600): Chaos and Violence in Europe

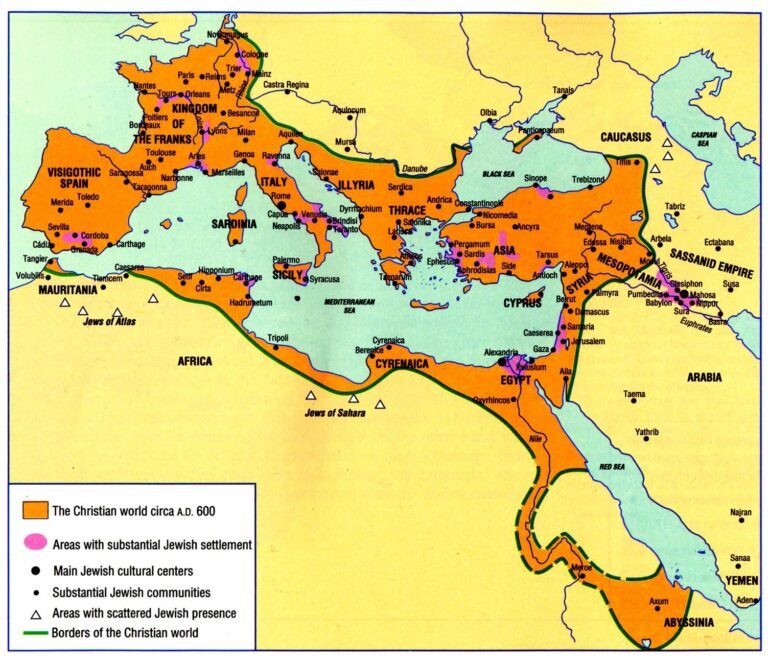

Emperor Constantine established Christianity as the official religion of the Roman Empire in 312. Then the Church began pursuing Christian nonconformist movements including the Manichaeans, Montanists, Ophitans, Priscillianists, and others.

These Christian sects are little known today since the Catholic Church was exceedingly effective in obtaining their writings, occupying their places of worship, banishing their leaders, and putting an end to them as dissenting Christian groups.

After attacking all non-Catholic Christian sects, the Catholic Church then began going after traditionalist pagans who revered Greek and Roman gods. From 391–392, the Byzantine Empire forbade the practice of traditional Roman religion in either public or private settings, under penalty of execution or exile.

The Empire returned its focus to the Jews after 418. Jewish marriage to a non-Jew was forbidden, and Jews were barred from serving in the government, the military, or holding positions of authority such as judges. Jews were forbidden from creating brand-new synagogues, remodeling existing ones, and converting non-Jews to Judaism. Additionally, the Byzantine Emperor destroyed the “patriarchate” in 429, which had developed following the fall of the Temple in Judea in 70.

Feudal Europe (600-1000): Prosperous Times for Jews

In general, during the early Middle Ages in Europe, Jews enjoyed a moderate level of freedom and prosperity. Forced Jewish conversions were forbidden by Pope Gregory the Great (591). Both Theodoric the Great (ruler of Italy from 454-526) and Charlemagne (ruler of France and western Germany from 742–814) allowed Jews to dwell in their realms, primarily for economic reasons.

William the Conqueror invited Jews to England in 1066. Jews were exempt from the feudal system and were not permitted to own ties to land or join guilds of artisans. Jews became money lenders since Christianity outlawed lending money with interest, making them attractive as traders and financiers in Christian Europe.

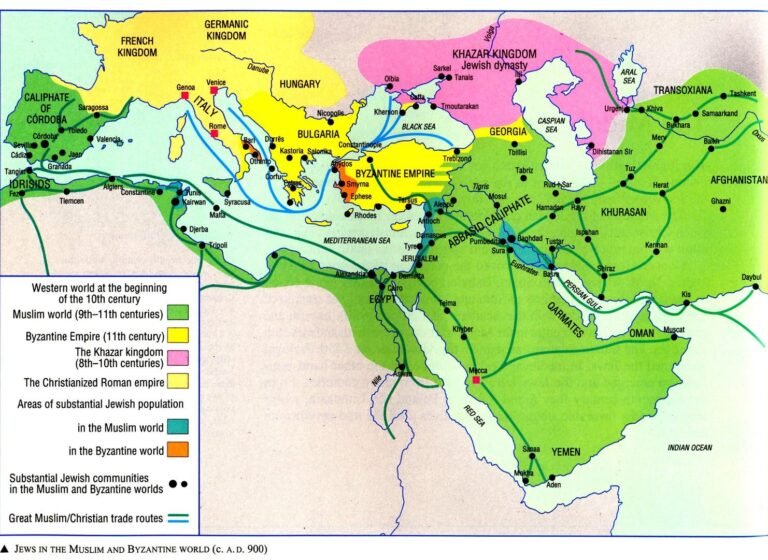

Islamic Empire (700-1200): Golden Age for Jews

Beginning around the middle of the 9th century, Jews were extensively tolerated and welcomed under Islamic rule along the southern and western margin of the Mediterranean Sea and east beyond the Caspian Sea. Muslims offered Jews and Christians immunity from military duty, access to their legal systems, and assurances of the security of their possessions. Islamic lands covered what is now Iran, Iraq, Turkey, western Russia, the Arabian Peninsula, northern Africa, Spain, Sicily, and Sardinia in Europe.

A Golden Age was experienced by Jews. They contributed much to Arab civilization and flourished there as intellectuals, scientists, statesmen, philosophers, and poets. Jews and Arabs coexisted peacefully and respectfully for many centuries. Both the Jewish Golden Age and the Golden Age of the Muslim Empire came to an end in the middle of the twelfth century with the reconquest by the Christians.

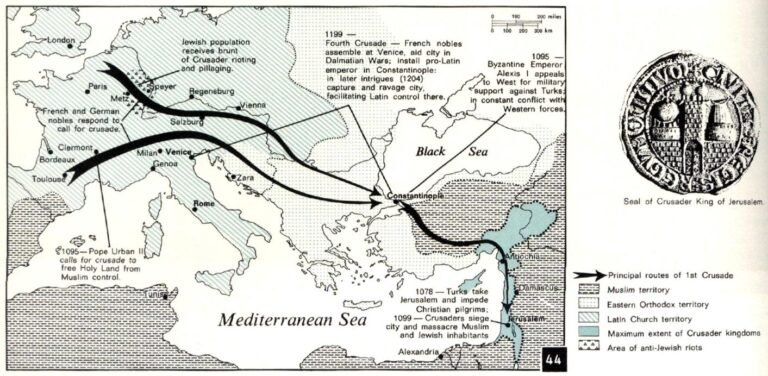

The Crusades (1095-1272): Jews as a Targeted Group

When feudalism ended, Christians seized the jobs that the Jews had previously held in the economy. Additionally, the Church also became less accepting of religious liberty.

To liberate the Holy Land and convert Jerusalem into a Christian sanctuary, the Crusades were fought. Jews, Muslims, scientists, and even suspected Christians were turned into enemies in Europe as a result of this religious zealotry. The first Crusade took place in 1095, while the eighth and final one lasted from 1270 to 1272.

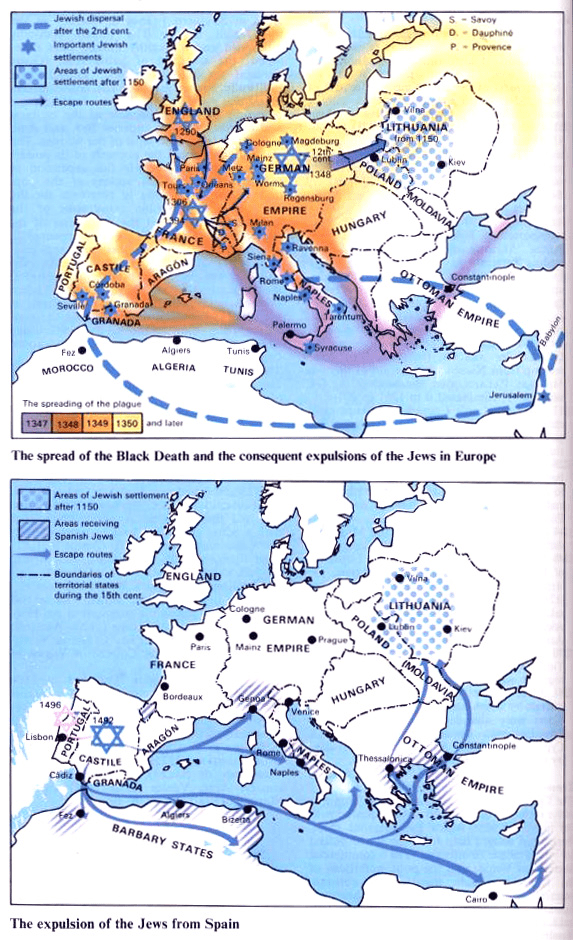

The High Middle Ages (1200-1500): Struggles in Europe and Settlement in Poland

With the advent of Christian rules in various parts of Europe, Jews continued to face many difficulties. They were required to wear specific clothing, insignia, or recognizable conical caps to set them apart from other people, according to the decree by Pope Innocent III in 1215.

Jews were charged with desecrating the Host, the consecrated bread given forth during the Eucharist, from the 13th through the 16th century. It is now known that as bread starts to go bad, a red mold can start to grow on it, giving the blessed bread the appearance of dripping blood. The first of a series of antisemitic atrocities happened in Belitz, Germany, in 1243 with the excuse of profaning the Host.

In the 14th century, Europe experienced a string of catastrophes, including terrible starvation, bad harvests, and the Black Plague. With the spread of superstitions and prejudice, Jews were blamed for all these hardships. Throughout Europe, the Jews were gradually confined to ghettos (confined spaces for minorities where they are forced to live).

During this period, Polish kings welcomed Jews and issued charters outlining their legal rights. Hence, Jews from all around Europe kept moving to Poland, where the population grew 10 times higher in just 100 years.

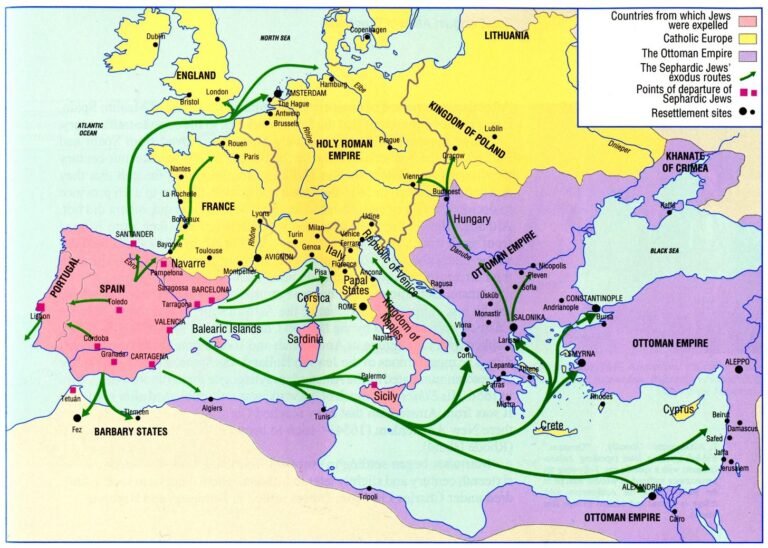

The Early Modern Period (15th-17th Century): Greater Tolerance of Jews in Protestant Nations

Europe underwent a drastic social and economic transformation during the Protestant Reformation of Christianity in 1521. Jews were permitted to return to nations where they had been banished centuries earlier if it was in that country’s economic interest. The Catholic countries were still intolerant of the Jews on religious grounds.

A thriving Jewish community started to emerge in Holland as a result of the freedom of religion granted to Jews starting in 1579. Jewish bankers were appointed to important posts like finance ministers between the 15th and 18th centuries in Germany and modern-day Austria.

Emperor Joseph II abolished the Jewish badge allowing Jews in the Hapsburg regions of Austria, Hungary, Bohemia, and Moravia to leave the ghetto, learn any trade, conduct business, and enroll in public schools and universities.

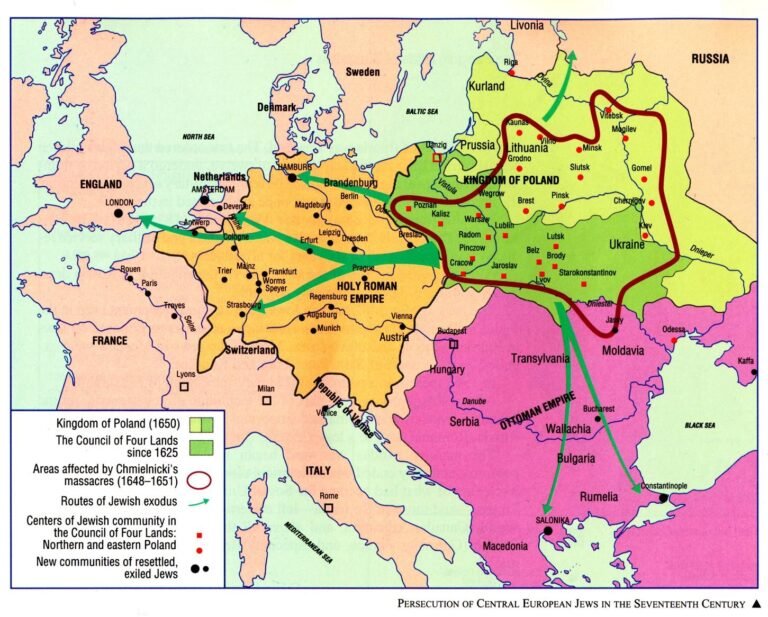

The Early Modern Period (17th to 18th Century): Fall of Poland as the Epicenter of the Jew

Poland rose to prominence as a hub of Jewish prosperity in the 15th and 16th centuries. This prosperity persisted up until the second half of the 17th century when a string of massacres carried out by Cossacks mercilessly murdered both Jews and non-Jewish Poles.

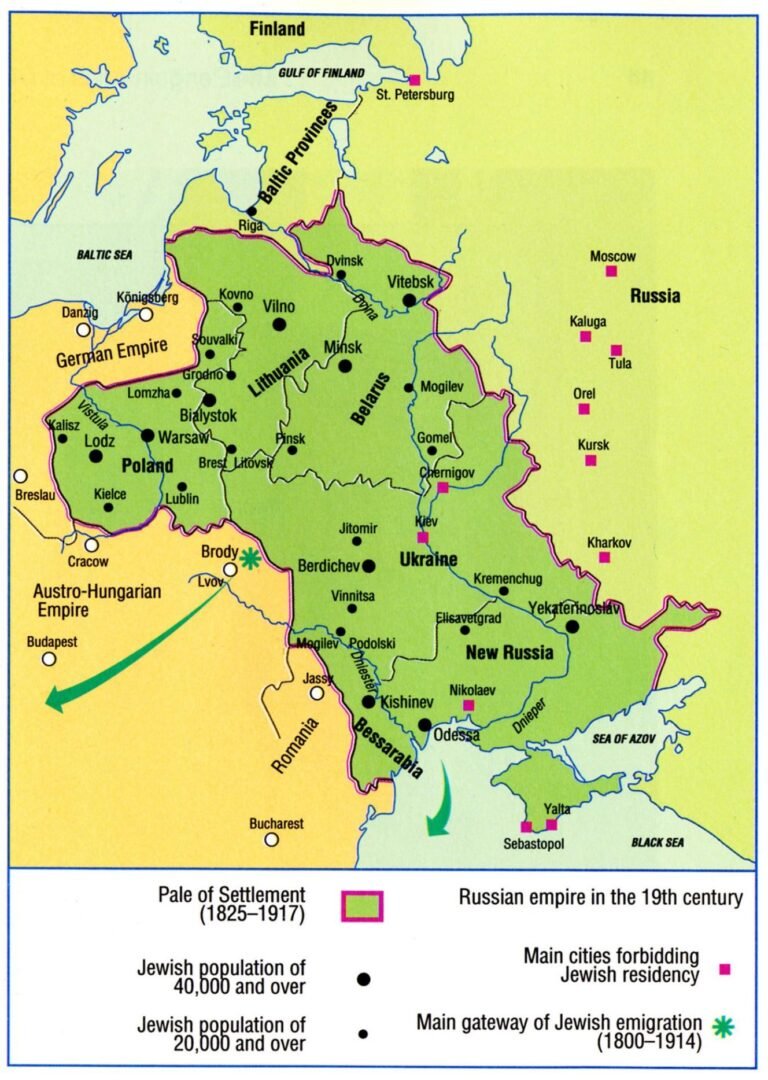

Then, a second Cossack rebellion, two Swedish invasions, and a conflict with Turkey devastated Poland. When Poland was split into three separate countries in the 17th century, Russia, Germany, and Austria all claimed control over the country’s Jews.

As Russia’s western border extended westward, more Jews were absorbed into a nation that was intolerant of them. Jews could only reside in the region along the western Russian border, also known as the Pale of Settlement, under a decree made by Catherine the Great in the late 17th century. In 1772, more Jews were living in the Pale than anywhere else in Europe.

The Modern Period (18th to 19th Century): New Freedoms and Migrations

Around the turn of the 18th century, revolutions were taking place in France, Germany, and Italy that overthrew monarchies and established democracies, granting their subjects new liberties and equal rights. In France, Italy, and Germany, Jews were freed. However, in Italy and Germany, the liberties and equality that the revolution provided to Jews and other citizens were quickly revoked by counterrevolutions. Jewish freedom was comprehensive and permanent in Britain and Holland.

The position of the Jewish population in western and central Europe was enhanced by the economic growth and opportunity of the 19th century. Jews moved largely from less developed areas to cities.

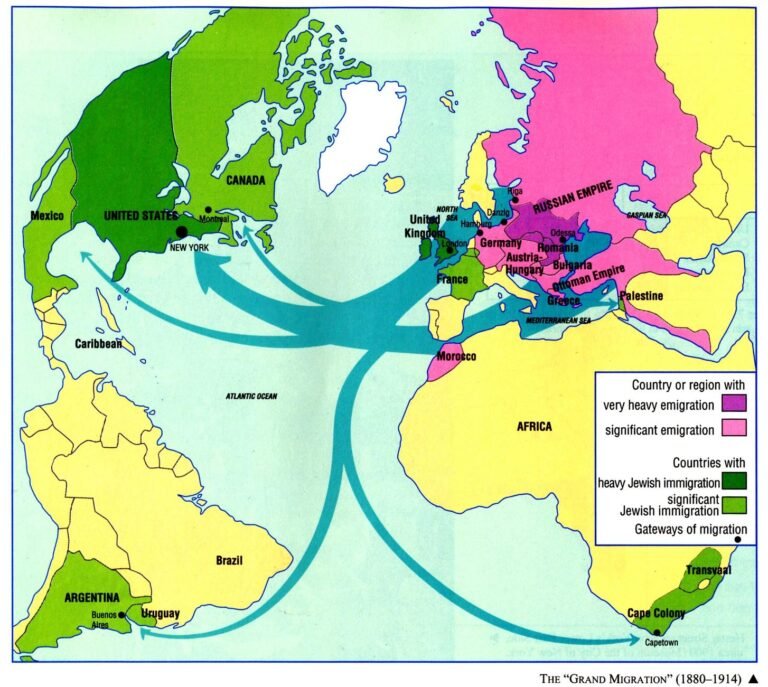

A few million Jews emigrated from Russia between 1881 and 1917 in search of a better life. A little more than 2 million immigrant households relocated to the United States, 200 thousand to Great Britain, 300 thousand to other parts of Europe, 100 thousand to Canada, and 40 thousand to South Africa. A few thousand migrated to Palestine.

World War I (1914 to 1918)

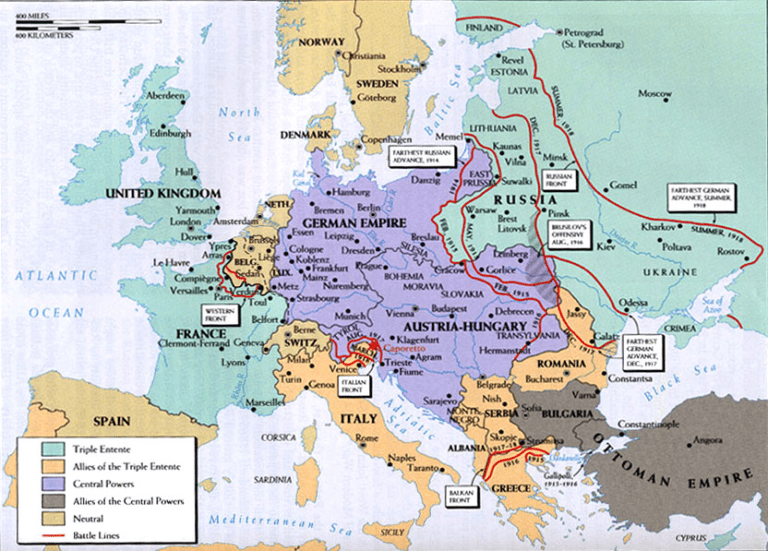

World War I (WWI) had a profound impact on the Jew population while nearly four million of them lived in the areas where the war on the eastern front between Russia and the Central Powers (Germany and Austria) was fought. They joined the war to show their allegiance to their respective nations. Almost half a million joined the Russian force while 100 thousand joined the German force.

Despite this large enlistment, the Jews in both nations were accused of evasion and profiteering, and official investigations were launched. Due to the Jews’ open animosity toward the oppressive Russian Tsar, suspicions about their loyalty were also raised in Russia’s two ally countries England and the United States. Numerous recently arrived immigrants from Russia refused to enlist. On the other hand, Jews of German origin were required to sign humiliating public declarations of loyalty in both England and the United States.

Despite the World Zionist Organization (Jewish nationalist international organization) proclaiming itself neutral, the majority of Jewish leaders supported Germany and the Austro-Hungarian Empire. German Jews all over the world established the “Committee for the East” to spread pro-German propaganda. Hermann Cohen, a Jewish philosopher, traveled to the United States in 1915 to urge the Jewish community to lobby the American government to support Germany in the war.

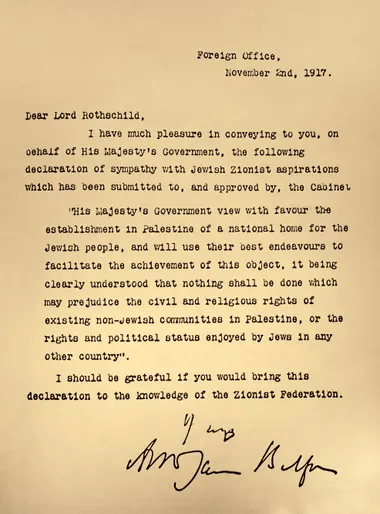

To gain the United States’ support in the war, the British government then reached out to the Zionist Organization’s pro-English minority to gain their support, which influenced the publishing of the Balfour Declaration in November 1917.

The Balfour Declaration marked the first significant political victory for Zionism. It was a letter written by British Foreign Secretary Arthur Balfour to British Zionist leader and banker Lionel Walter Rothschild, in which he expressed the British government’s support for a Jewish homeland in Palestine.