Mohammad Tanvir Hossain –

The Israel-Palestine conflict is one of the most complicated and divisive issues in the world today, which started as a regional conflict one hundred years ago. a struggle for the same territory between two quite dissimilar parties. It has national, political, geographical, cultural, and religious roots. Israelis and Palestinians both want the same thing: land. To better understand its reasons and underlying issues, let’s retrace the Israeli-Palestinian conflict through a historical journey.

The Partition of Palestine and Its Aftermath:

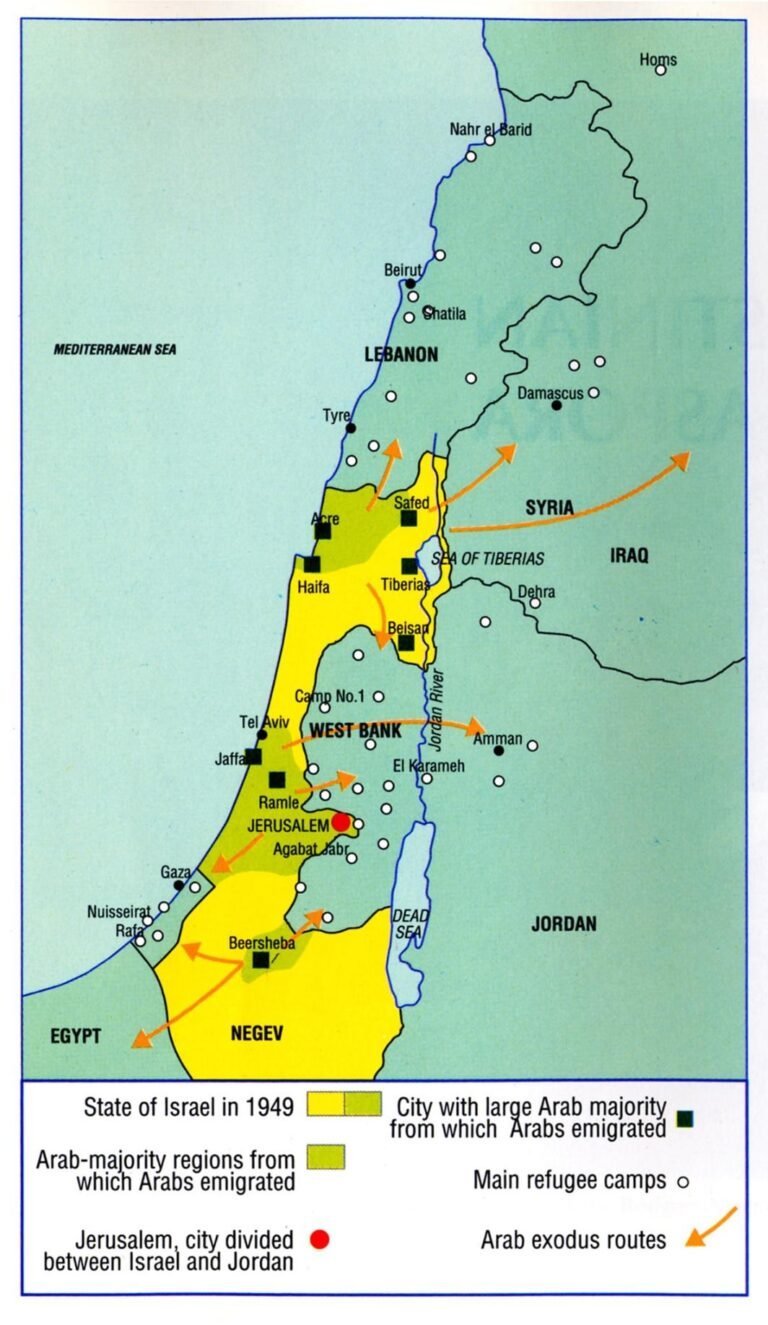

The conflicted state of Israel and Palestine in 1948-49 created an enormous number of Arab refugees. Rich businessmen and prominent urban figures from Jaffa, Tel Aviv, Haifa, and Jerusalem went to Lebanon, Egypt, and Jordan, while the middle class opted to settle in Arab-only communities like Nablus and Nazareth. The vast majority of fellahin (peasants) ended themselves in camps for refugees.

More than 400 Arab villages vanished, and the Arab population in the coastal cities – particularly Jaffa and Haifa – basically disappeared. Palestinian life relocated to the Arab cities in the region’s steep east, which came to be known as the West Bank.oha

The term “Palestinian”:

The Arab population of Palestine never had a separate state for themselves, hence the term “Palestinian” never existed at an early age. They used to consider themselves to be a part of the greater Arab or Muslim society. Prior to the creation of Israel, the Arab people of Palestine were referred to as Palestinians by Jews and outsiders only.

Arabs in Palestine started using the name “Palestinian” just before World War I to denote the nationalist notion of the Palestinian people. However, following 1948, and especially after 1967, the name grew to represent not only a place of origin but, more significantly, a sense of a shared past and future in the form of a Palestinian state.

Palestinian Citizens of Israel:

At the time of the creation of the Israeli state, there were about 1.5 lac Arabs living in Israel. This group was made up of around one-eighth of all Palestinians. Most of them resided in the western Galilee settlements. They were compelled to forsake agriculture and work as unskilled wage laborers in Jewish enterprises and construction firms.

They theoretically had the same civic and religious rights as Jews as Israeli citizens. However, in reality, they were subject to a military regime that severely constrained their freedom of movement and political choices until 1966. Palestinian inhabitants lived in isolation from other Arabs for nearly 20 years.

West Bank (and Jordanian) Palestinians:

The Jordanian monarchy took the opportunity in the events of 1948–49 to increase Jordanian territory by incorporating Palestinians into its population and giving them a new, inclusive Jordanian identity. In addition to providing education, it granted citizenship to the Palestinians in 1949.

However, conflicts soon emerged between the native Jordanians and the more intelligent and talented foreigners. While the fellahin (peasant) populated the UN refugee camps, wealthy Palestinians lived in the towns on the east and west banks of the Jordan River and vied for posts in the government.

Two-thirds of the people in Jordan were Palestinian. Representatives from the West Bank were given half of the seats in the Jordanian Chamber of Deputies, but the West Bank’s residents and those from the region east of the Jordan River had very different social, economic, educational, and political backgrounds, making it difficult to integrate the two regions.

Other than the famous families that the Jordanian monarchy preferred, Jordanian Palestinians tended to favor the radical pan-Arab and anti-Israeli views of Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser rather than the more circumspect and accommodative posture of Jordan’s King Hussein.

Palestinians in the Gaza Strip

The Gaza Strip was under Egyptian control for almost 20 years (1948–1967). In general, the Egyptian government was oppressive. Their denial of citizenship to the Palestinians made them stateless (without nationality). However, they were permitted to enroll at Egyptian universities and occasionally vote in municipal elections.

Though Amin al-Husseini established a Government of All Palestine in Gaza strip in 1948, it was short-lived because of being wholly dependent on Egypt. Palestinian Arab nationalism was greatly weakened in the 1950s by the failure of this endeavor and al-Husseini’s lack of credibility due to his participation with the Axis powers (Germany, Italy, and Japan) during World War II.

In absence of agriculture and industry, Gaza emerged as an Egyptian duty-free port. Although some Palestinians in the Gaza Strip were able to leave the region and pursue an education and a profession elsewhere, the majority were forced to remain there despite the region’s dearth of resources and work opportunities.

The United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA) Camps for Palestine Refugees in the Near East:

Being formed in December 1949, UNRWA constructed a total of 53 refugee camps on both sides of the Jordan River, as well as in the Gaza Strip, Lebanon, and Syria to support the 6.5 lac or more Arab refugees. Tents were initially used by refugees in the makeshift camps, but after 1958, modest dwellings made of concrete blocks with iron roofs took their place. Initially, refugees lived in tents, but after 1958, modest dwellings made of concrete blocks with iron roofs took their place.

The circumstances were incredibly difficult with extreme hot and cold weather conditions. Frequently, multiple families had to share one tent. Even though the refugees were given free housing and access to necessities like water, healthcare, and education, there was still a lot of poverty and suffering. Despite UNRWA’s efforts to integrate the Palestinians into the struggling economies of the host countries, employment was rare.

Palestinians Outside Mandated Palestine:

Few Palestinians were able to obtain citizenship in Syria, Iraq, Lebanon, and the Persian Gulf states, despite the fact that many found work there. They frequently experienced discrimination, and the governments of their individual countries constantly monitored them in an effort to curtail their political activity.

The Resurgence of Palestinian Identity:

The experiences of exile and the events of 1948 had an impact on the political and cultural life of the Palestinian people. Palestinians residing outside of Israel were given the primary responsibility for reconstruction, including those living in the West Bank, Gaza Strip, and new Palestinian settlements outside of the former British territory. Palestinians residing in Israel continued to be in a tumultuous, isolated condition and were viewed with skepticism by both Israelis and other Palestinians.

Even while four out of every five Palestinians had remained inside the boundaries of the former British mandate, the new leaders were disproportionately drawn from those who had migrated to Western and various Middle Eastern countries. By the middle of the 1960s, a youthful, educated leadership had replaced the discredited traditional local and clan leaders, despite Israeli attempts to thwart the creation of a fresh Palestinian identity.

The Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO):

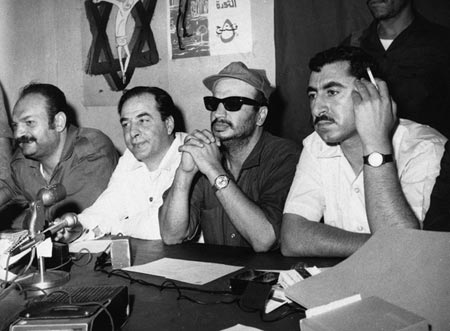

The PLO was founded as a result of an Arab summit held in Cairo in 1964. Being a political umbrella body for a number of Palestinian organizations, it became the sole representative of the entire Palestinian population. Ahmad al-Shukeiri served as its first head. The PLO outlined its fundamental beliefs and objectives in its 1968 charter (the Palestine National Charter, or Covenant). The three most significant objectives were the right to an independent state, the complete liberation of Palestine, and the eradication of the State of Israel.

The Palestine National Council (PNC) was created to act as the PLO’s supreme body or parliament. In the beginning, the PNC was made up of civilian representatives from different regions, such as Jordan, the West Bank, and the Persian Gulf states; however, in 1968, guerrilla organization representatives were also added.

Fatah and Other Guerrilla Organizations:

The Palestine National Liberation Movement (Ḥarakat al-Taḥrīr al-Waṭanī al-Filasṭīnī), sometimes known as Fatah due to the Arabic initials being reversed, was established several years prior to the founding of the PLO. Both PLO and Fatah trained guerrilla groups for attacks on Israel.

In addition to Fatah, several other groups started to take shape in the late 1960s. The Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine (DFLP), the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine-General Command (PFLP-GC), and al-Iqah (backed by Syria) were the most significant ones. These groups cooperated inside the PLO despite having opposing ideologies and strategies. Fatah leader Yasser Arafat assumed leadership of the Palestinian national movement in 1969 when he was elected as the executive committee’s chairman of the PLO.

The guerrilla organizations were united in their rejection of any political settlement that did not include what they perceived to be the complete liberation of Palestine and the return of the refugees to their homeland. However, according to Palestinian officials, in addition to destroying Israel and ridding Palestine of Zionism, they also aspired to create a state devoid of religious divisions where Jews, Christians, and Muslims could live side by side in peace.

Most Israelis questioned the sincerity or viability of this objective and perceived the PLO as a terrorist group out to destroy both the Zionist state and Israeli Jews.

1967 Third Arab-Israeli War (The Six-Day War):

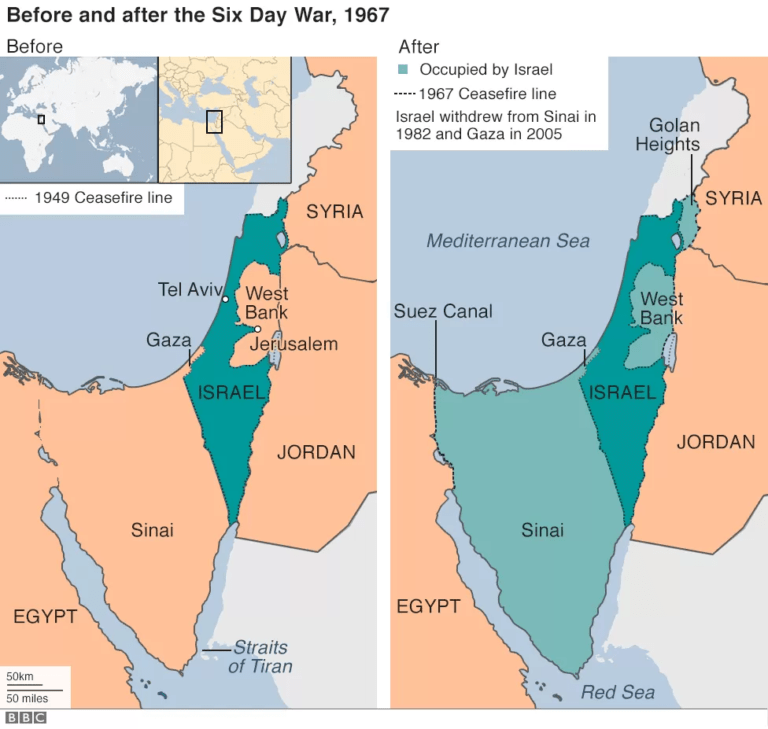

The Six-Day War was a brief but bloody conflict fought in June 1967 between Israel and the Arab states of Egypt, Syria, and Jordan. After years of diplomatic tension and clashes with its neighbors, Israel’s Defense Forces launched airstrikes that severely damaged Egypt’s and its allies’ air defenses. Then, following a victorious ground offensive, Israel conquered the Golan Heights from Syria, the West Bank, and East Jerusalem (known to Israelis by the biblical names Judaea and Samaria) from Jordan, and the Sinai Peninsula and Gaza Strip from Egypt. A U.N.-brokered ceasefire brought the short war to a close, but it had a lasting impact on the Middle East’s geography and caused geopolitical tension.

Following Israel’s victory, more than 2.5 lac Palestinians fled to the Jordan River’s eastern bank, sparking yet another migration. However, there were still about 3 lac Palestinians living in the Gaza Strip and 6 lacs in the West Bank. As a result, 12 lac Arabs (including the 3 lacs already living in the State of Israel) were ruled by Israel with its 30 lac Jewish population.

In addition, a movement emerged among Israelis that promoted settling the seized territories, notably the West Bank, as a component of the Jewish heritage in the Holy Land. In the decade after the war, a number of thousand Israeli Jews relocated there.

Jordan’s Reaction After the Six-Day War:

In 1970, King Hussein of Jordan ordered the PLO fighters to leave Jordan, and in 1973, he refused requests from Egypt and Syria to join their conflict with Israel. Jordan and Israel agreed to a peace accord in 1994 after years of confidential negotiations.

1973 Fourth Arab-Israeli War (Yom Kippur War):

On 6th October 1973, Egyptian and Syrian forces launched a coordinated attack against Israel on Yom Kippur, the holiest day in the Jewish calendar, hoping to win back territory lost to Israel during the Six-Day war in 1967. Taking the Israeli Defense Forces by surprise, Egyptian troops swept deep into the Sinai Peninsula, while Syria struggled to throw occupying Israeli troops out of the Golan Heights. Israel counterattacked and recaptured the Golan Heights. A cease-fire went into effect on 25th October 1973 by the UN.

Following the ceasefire, oil-exporting Arab nations made the decision to punish the US and Israel’s allies by raising oil prices by 70 percent and cutting back on output by 5 percent, which brought on the 1973 first oil crisis. Israel gradually gave back the Sinai to Egypt in response to international pressure, but it nevertheless kept sovereignty over the Palestinian territories, where colonization accelerated, especially in East Jerusalem.

Yom Kippur War was a disaster for Syria. The unanticipated Egyptian-Israeli cease-fire left Syria vulnerable to military defeat, and Israel expanded its control over the Golan Heights. In March 2019, the United States became the first country to recognize Israeli sovereignty over this territory. The rest of the world still sees the land as Syrian but under Israeli occupation.

The PLO’s Rise as a Revolutionary Force:

The PLO, led by Fatah, behaved as a state-in-the-making during the 1970s and 1980s and frequently attacked Israel militarily. After the Yom Kippur War, Fatah quickly ingratiated and organized the newly united Palestinian community with the help of its organizations and social services.

Despite being widely acknowledged as the representation of the Palestinian national movement, the PLO lacked internal cohesiveness. It promoted Palestinian autonomy and identity, but due to external pressures, the leadership had to maintain a certain level of distancing from Palestinian daily life. Because of this, enforcing a single policy was challenging.

Start of Negotiations:

Numerous intensive negotiations on Arab-Israeli problems took place in the late 1970s. The Arab governments supported Palestinian involvement in a broader agreement that called for Israeli withdrawal from territories it had been occupying since the 1967 Middle East conflict and the establishment of a Palestinian state in the West Bank and Gaza Strip.

The US attitude toward the Palestinians appeared to be changing. American President Jimmy Carter first mentioned the need for a Palestinian homeland in March 1977, and he later emphasized the importance of the Palestinians’ involvement in the peace negotiations. Despite continuing to oppose the PLO’s involvement in the peace process, the Israeli cabinet resolved to refrain from scrutinizing the backgrounds of Palestinians who might join delegations from Arab nations.

The Camp David Accords and the PLO:

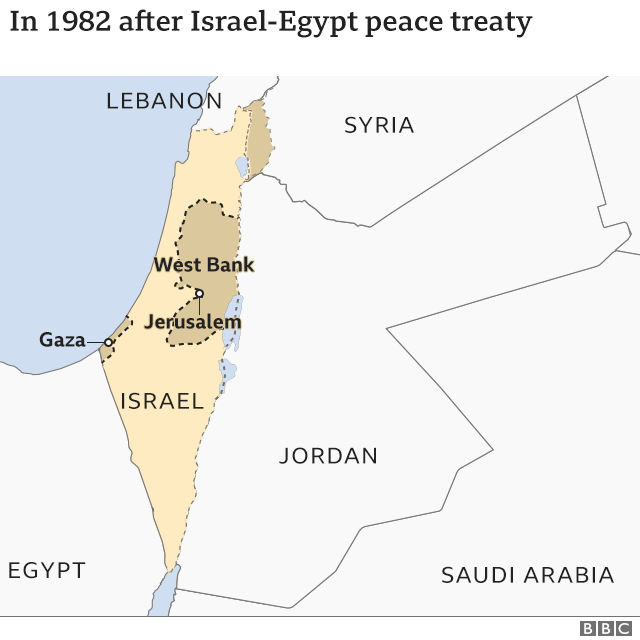

The Camp David Accords, between Israel and Egypt, was signed on 17th September 1978. Brokered by US President Jimmy Carter, it was the first peace treaty between Israel and any of its Arab neighbors. The agreements called for the creation of a self-governing authority in the West Bank and Gaza Strip as well as a transitional period of no more than five years after which the locals would be granted autonomy.

The PLO was acknowledged by the Soviet Union as the sole legitimate representative of the Palestinians during the time of the peace negotiations. In June 1980, the countries of western Europe also declared their support for PLO participation in peace talks.

The PLO persisted in seeking diplomatic recognition from the US, but the Carter administration upheld a secret promise made to Israel by the late US secretary of state Henry Kissinger not to interact with the PLO as long as it refused to give up terrorism and acknowledge Israel’s right to exist.

The Dispersal of the PLO from Lebanon:

Israel invaded Lebanon on 6th June 1982, claiming to be ending attacks on its land with the goal of ousting the PLO and promoting the establishment of an Israeli-friendly Lebanese administration. Israeli troops routed PLO and Syrian forces, and the remaining PLO forces were confined to west Beirut. Following a protracted siege and bombardment by Israel, around 11 thousand Palestinian militants were permitted to depart Beirut for a number of destinations under international guarantees for their own safety and the safety of their dependent civilians in July and August 1982.

Despite these guarantees, Israeli forces nonetheless permitted the Phalangists, Israel’s right-wing allies in Lebanon, to enter the Sabra and Shatila refugee camps in Beirut, where they slaughtered hundreds of Palestinian and Lebanese civilians.

Although not all PLO militants were forced to leave Lebanon, the infrastructure of the organization in the south of the nation was destroyed, and Arafat’s move from Beirut to northern Lebanon signaled the PLO’s military and political presence in the nation coming to an end. It was unable to openly operate from any of the countries that bordered Israel.

A faction within Fatah, supported by Syria, emerged and posed a challenge to Arafat and the other PLO leaders. Arafat was expelled from northern Lebanon in December 1983 by the Syrians and PLO allies of theirs.

After settling down close to Tunis, Tunisia, Arafat turned to diplomatic attempts. He asked for support from Egypt and Jordan against Syria. Additionally, he looked to King Hussein of Jordan to negotiate with the US and Israel to create a Palestinian ministate in the West Bank inside of a Jordan-Palestine confederation, a proposal that had been supported by the PLO’s main factions since the early 1980s. The Palestine National Council explicitly proclaimed this policy in Amman in November 1984.

Years of Mounting Violence:

Numerous Israeli actions exacerbated Palestinians’ sense of separation from the Jewish majority. Jewish ultranationalists called for the forcible eviction of Palestinians from the occupied territories in addition to increasing their calls for new Jewish colonies and the annexation of the West Bank. In 1985, the Israeli Knesset (parliament) approved a law outlawing any political group endangering national security, i.e., anti-Zionist groups. This confirmed the belief of the majority of Israeli Palestinian citizens that no legitimate political party could appropriately represent their social, political, and economic interests.

Israeli settlers and Palestinians both increased their attacks on each other from 1986 to 1987. One-third of the territory in the Gaza Strip and more than half of the area in the West Bank were under Jewish control by 1988. There were roughly 1 lac Israelis living in the West Bank.

Palestinian youth had grown up under Israeli occupation in the late 1980s. Their economic standings were poor and dependent on Israel’s economy, while their civic rights were restricted. Every day, between 1 and 1.2 lac Palestinians entered Israel through the occupied territories to work. They had little faith in Arab governments and the PLO and started to rely more on their own initiatives.

The First Intifada:

The Palestinians engaged in small-scale protests, riots, and infrequent acts of violence against Israelis during 1987 as a result of not receiving effective support from other nations and also Israel. In response, the Israeli government closed universities and made arrests and deportations.

Early in December 1987, there were widespread riots and protests in the Gaza Strip that lasted for more than five years. The intifada, which is Arabic for “shaking off”, was the result of this rebellion and ushered in a new period of Palestinian mass mobilization.

The intifada used extremely sophisticated tactics. Union-organized strikes, boycotts, closures of businesses, and protests were held in one area of the territories before being moved to another after Israel had reclaimed its local authority there. Palestinian refugee camps served as important hubs for the resistance, although Palestinian Arabs in more affluent environments also took part, and some Palestinian citizens of Israel expressed support for the uprising’s objectives.

More than 3 hundred Palestinians were killed within the first year of the intifada, 11.5 thousand were injured (almost two-thirds of whom were under 15), and numerous others were detained. Israel imposed curfews, burned homes, and closed universities and schools, but it was unable to put an end to the rebellion.

The International Red Cross estimates that by the middle of 1990, Israeli security forces had killed more than 8 hundred Palestinians, more than 2 hundred of whom were under the age of 16. A total of 16 thousand of Palestinians were incarcerated. Comparatively, there had been fewer than 50 Israeli fatalities. Several hundred Palestinians were slain by their fellow countrymen in the occupied territories after being accused of working with Israel. Israel was engulfed in political deadlock.

PLO Declaration of Independence:

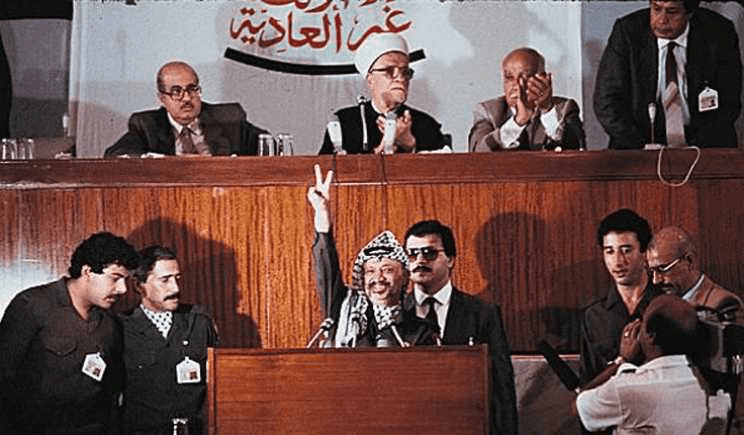

Midway through 1988, Yasser Arafat initiated diplomatic action in an effort to position himself as the sole figurehead to unify and represent the Palestinian people. He was successful in getting the Palestine National Council (PNC) to declare a proclamation of independence for the state of Palestine in the West Bank and Gaza Strip.

On 15th November 1988, Arafat declared the state (without specifying its boundaries). Within a few days, the government-in-exile had received recognition from more than 25 nations (including the Soviet Union and Egypt but excluding the United States and Israel). An entirely new chapter in Palestinian-Israeli relations began in the latter weeks of 1988. Arafat declared in December that the PNC opposed and rejected all types of terrorism and acknowledged Israel as a state in the region.

He spoke in a special UN General Assembly meeting held in Geneva and suggested holding an international peace conference under UN authority. He formally acknowledged the State of Israel by openly approving UN resolutions 242 and 338. Despite Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Shamir’s declaration that he was still not willing to engage in negotiations with the PLO, the US government made the announcement that it would begin those negotiations.

1993 The Oslo Accords:

The Oslo Accords, also known as the Declaration of Principles on Interim Self-Government Arrangements, was signed at the White House on 13th September 1993 and marked a turning point in the Middle East peace process.

The PLO repudiated terrorism and acknowledged Israel’s right to coexist in peace, and Israel accepted the PLO as the Palestinians’ official representative. Both parties agreed that over the course of five years, the West Bank and Gaza Strip would be governed by the Palestinian Authority (PA), which would be constituted. After then, negotiations on the future of Jerusalem, the boundaries, and refugees would take place.

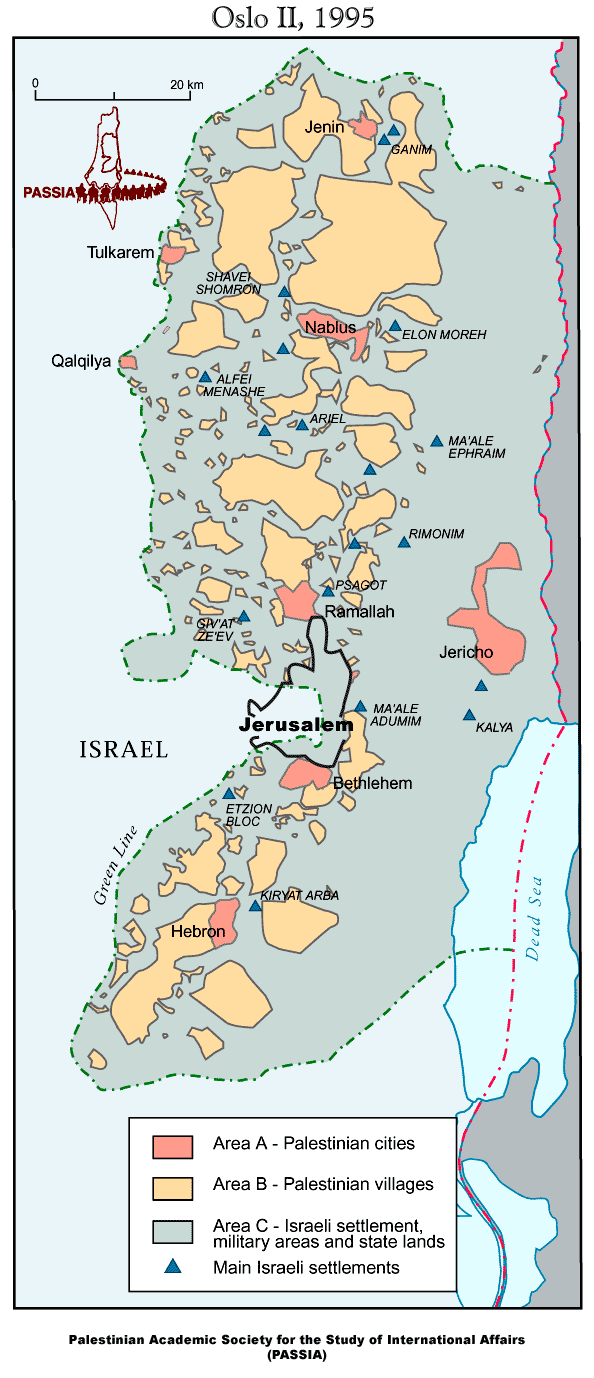

1995 The Oslo Accords II:

Following lengthy negotiations, Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin and PLO Chairman Yasser Arafat signed an accord known as Oslo II in Washington on 28th September 1995. It dealt with the expansion of Palestinian authority over the West Bank. Israel agreed to leave six West Bank cities and withdrew partially from Hebron. It also made provisions for Palestinian police deployment and elections for the Palestinian Legislative Council. The Knesset (Israeli parliament) approved the agreement by a vote of 61 to 59 on 6th October, 1995.

The Gaza Strip and the West Bank were to be divided into four zones :

-

Zone A: comprising the Gaza Strip and 3 percent of the West Bank with 8 cities. In this zone, the Palestinian Authority (PA) would be responsible for civil matters and security.

-

Zone B: comprising 24 percent of the West Bank and was essentially rural in character, including West Bank villages where the PA would be responsible for civil affairs and for public order, with Israel reserving control of security.

-

Zone C: comprising 73 percent of the West Bank, where the majority of the Jewish colonies are located. This would be entirely under the control of Israel.

-

Zone D: made up of frontiers, road interchanges, and military outposts responsible for the security of the Jewish colonies.