23rd June 2019. The river Karnaphuli was flowing towards the Bay of Bengal like it had been flowing since the prehistoric period. Many loaded cargo ships with hundreds of containers were leaving Bangladesh, many were reaching Chattogram port from several thousand miles distance. Those ships were continuously blowing their horns.

This sound was very familiar to the people living on the banks of the river Karnaphuli. However, a young mechanical engineer, who had been living near the estuary for the past 1 year, could not be habituated to this sound yet. He often stood by the side of the river and tried to count the number of ships, but never succeeded.

That day he was also standing and looking towards a small boat dancing on the waves. It was a special day for him. He was done with his first power plant erection project, and the 314-megawatt Heavy Fuel Oil (HFO) based plant started its commercial operation that day.

A person without such project experience would never be able to realize an engineer’s feelings on the first commercial operation day of a fresh-from-the-oven project. It is a mixed feeling of relief and melancholy at the same time. Relief from the enormous pressure of project completion deadlines, hourless duty, endless noise of metal cutting, welding, and drilling, shouting of the contractor supervisors, operation of the heavy lifting crane and dump truck, and especially hundreds of people moving here and there. And who would not fall into melancholy after being so relieved from that much pressure?

In Bangladesh, almost 50 percent of the total consumed electricity is generated by the private sector. This writing is reminiscent of an erection engineer of a private sector power plant, and later operation and maintenance engineer of the same plant. The journey was intense, at the same time a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for a mechanical engineer.

Before starting the discussion, the systems of electricity production and consumption in Bangladesh are needed to be described in short. Let us go with some specific questions and answers.

-

Who does consume electricity in Bangladesh?

-

People of the country. Consumers are grossly divided into residential and industrial.

-

Who does provide electricity?

-

Government of Bangladesh. Besides the government, there may be some private electricity generation facilities like the small diesel generator of a shop or your home.

-

Which are the government organizations to take care of issues about electricity?

-

Bangladesh Power Development Board (BPDB) for all urban electrical connections and Bangladesh Rural Electrification Board (BREB) for all rural electrical connections.

-

What are the steps of the supply chain of electric power?

-

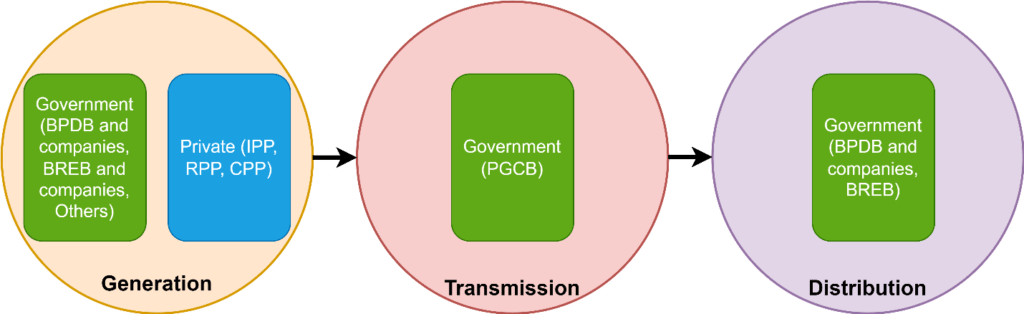

Three steps- Generation, Transmission, and Distribution.

-

Who does generate electricity?

-

Power plants. Those may be owned by the government (BPDB and BREB), government companies, or the private sector.

-

What are the types of private power plants based on the agreement with the government?

-

IPP (Independent power plant): Long-term agreement with the government (15 years or more). Their produced electricity is supplied to the national grid and bought by the BPDB.

-

RPP (Rental power plant): Short-term agreement with the government (1 year to 5 years). Their produced electricity is also supplied to the national grid and bought by the BPDB.

-

CPP (Captive power plant): Industries install these power plants for their use. Though they do not supply electricity to the national grid, they are also accountable to the government organization BERC (Bangladesh Energy Regulatory Commission) for their installation. In recent years, after meeting self-demand, some CPP sell their remaining electricity to the BPDB.

-

Who does transmit electricity?

-

Power Grid Company of Bangladesh (PGCB). This organization controls the transmission, national grid, and NLDC (National Load Dispatch Centre).

-

Who does distribute electricity?

-

BPDB and its distribution companies and BREB.

A flowchart can depict the overall systems of electricity in Bangladesh at a glance-

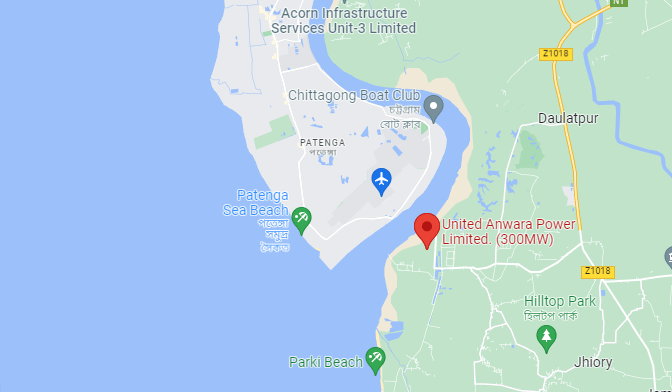

In this writing, I would be sharing some of my experiences of the erection, operation, and maintenance of the United Anowara HFO-based Power Plant which is listed as UAnPL in the BPDB power plant list. As already mentioned, the location of plant is in Anwara Upazilla of Chattogram district just near the estuary of the river Karnaphuli and the Bay of Bengal. The plant is running at its full capacity synchronizing with the national grid since June 2019.

During the erection period of a plant, an engineer gets burnt in the sun and wet in the rain. This is how a power plant gets shape from bricks, rods, and metal sheets. As an assistant project engineer, when I reached the project area crossing the river, I was bewildered! By the side of the river, large areas of land were being filled with sand. Some people, wearing white helmets, were moving here and there (later I could know the engineers wear white helmets), their faces were wrinkled in the sun; some laborers were unloading rods and sacks of cement brought by dump trucks, and three cranes were standing like giants. Some small huts made of corrugated iron sheets were standing side by side. Seeing my shocked face, probably the project manager himself came forward and received me, and asked me to sit in his office.

I came from Dhaka to Chittagong to join an office, but where was that office? The manager took me to a hut. A few plastic chairs were around a plastic table, a ceiling fan was hanging from bamboo, a laptop was on the table, and some AutoCAD drawings printed on A3 paper were kept. This was the project manager’s office. For someone with no experience working on an erection project, the scene was quite depressing.

After that, the environment gradually became bearable. The initial feeling of shock and despair slowly faded away. I accepted that project work was like that. Instead of talking in a whisper, I learned to scold loudly! Sometimes, I had to get the job done by the welders, fitters, riggers, and crane operators with threats and sometimes with pats on the back. I learned to sit with the workers in the dust and laugh with them. The work was progressing at full speed.

Fabrication drawings from Wartsila, Alfa Laval, and Triveni (they were the engine, boiler, and turbine manufacturers) were sent by email from their head offices. Accordingly, we sent BOM (Bill of Materials), and BOQ (Bill of Quantity) from the field, then the truck loaded with Corten, Mild Steel, and Stainless Steel plates arrived. These plates were then turned into large tanks and ducts. The contractor’s experienced foremen did all the fabrication as per the drawings. Engineers were checking the welding quality at this stage. The foremen would call the engineers whenever a drawing was not clear to them.

“Sir, if we cut this metal sheet in a triangular shape instead of a rectangle shape, the construction will be easier. What is your opinion?” In the beginning, I was very confused by this question, as fabrication drawing was a mystery to me too! I used to ask my manager. Slowly, I learned to visualize the 3D image in my mind by looking at the 2D drawing. Then I started to give the decision to modify it by myself.

Meanwhile, the civil department was building the base of engines, boilers, and turbines at a rapid pace. The electrical department was installing earthing cables and high voltage power cables. In the meantime, a steel structure stood on the engine base. For the first time, something as vast as a house was seen in the wasteland! Pipe modules, auxiliary modules, large ventilation fans, radiators, etc. started arriving in large containers. After one such container was emptied, we took chairs and tables inside it and built our new office. The appearance of this office was very royal in comparison to that hut!

I can still remember the day when the first engine and boiler arrived on a barge through the Karnaphuli river. How excited we were that day! Some were taking pictures, some were making videos as if the king came and entered his kingdom!

Since then, the influx of foreign engineers to the project increased. They were from different parts of the world – Finland, Italy, Germany, Brazil, China, and India. Then, the project proceeded with their expert advice. Many of them had 25-30 years of experience in their respective fields. How many stories I had shared with them, about the country, family, and their various experiences.

Time seemed to pass very quickly. Every day a new part of the power plant was getting visible. It looked like the fabrication and installation of everything was over. Various types of modification and remodification of the drawing were done, and the work of boiler-turbine piping was also completed. The boom of the 150-ton crawler crane had been standing above everything and watching us since the beginning of the project!

The electrical department gave the final touch at the end of all the work. All types of connection, automation, switchgear, and substation work had been completed. After the commissioning and test run, the much-awaited Commercial Operation Date (COD) came. We had to complete a 72-hour test in presence of BPDB. With worrying faces, all were waiting eagerly. Everyone, from the company owner to the top management, was present on those 3 days. High-ranked officials from BPDB were also present.

As the plant was running successfully, we just stood back and looked at the plant with a little pride, there might be even a little tear of joy in the corner of our eyes. I was a part of the team who were behind this plant standing like this!

Our 300-megawatt plant could supply 303 megawatts of electricity to the national grid for 96 consecutive hours. BPDB took 72 hours into their consideration, we passed with flying colors! We celebrated with a full plate of biryani and sweets. The next story is only about the operation and maintenance team.

So many stories happened in my first 12 months at Anwara. This whole time I came to the duty place at 9 am, and had to stay till 9/10 pm every day, even some days it was 2 am to go home! Meals were taken at the duty place, sitting on wooden benches in a hut. The recreation was nothing more than labor and engineers playing cheap pranks together. There was no official off day during the project time, quietly telling the boss to manage 1 or 2 days sometimes. Sunshine, rain, and public holidays, nothing could stop the work of the project.

Most of us had no idea after leaving the university that IC (internal combustion) engines could be used to run a large power plant. But the power plant in the private sector of Bangladesh means an engine-based power plant, be it a gas engine, or marine diesel (or HFO) engine. My university’s (BUET) own captive power plant was also engine-based, but it was only a few megawatts of capacity.

Almost everyone who takes an academic course on mechanical and electrical reads about Rankine Cycle and Combined Cycle. Water will evaporate in the boiler, the turbine will turn on that steam, the steam used in the turbine will be converted into water as a result of condensation, the water will be pumped and sent back to the boiler – this cyclical phenomenon is the Rankine Cycle. In a power plant, this cycle is coupled to an alternator or generator. The turbine turns the alternator, thereby producing electricity. Again, when the alternator is rotated directly with a gas turbine (GT), the high temperature obtained by burning gas in the turbine can be used to run a steam turbine (ST) cycle, this joint system is a Combined Cycle.

Although they are covered in the academic syllabus, instead of turbines, the engines are used as the prime mover of the alternator in most of the private power plants in Bangladesh (only Summit and Max Group have GT-ST). I was surprised to know this at the beginning of my power plant job.

Due to a shortage of gas as fuel, and a lack of considerable time and skill for the installation of turbines, the government decided to fill domestic electricity shortages by setting up quick rental power plants. State policies had encouraged private companies to set up engine-based plants from the beginning. And because it is possible to produce electricity with an affordable fuel like HFO, private companies have built a lot of power plants with marine engines or ship engines.

KPCL (Khulna Power Company Limited), built in Khulna around 1997, was the first HFO engine-based private power plant in Bangladesh. The plant was a joint investment by Summit and United Group and Finnish engine manufacturer Wartsila. After that many more private companies came into the power business of Bangladesh.

Let us go back to technical issues. HFO is a very annoying class of fuel! I estimate that this oil accounts for 80 percent of the physical labor involved in HFO plant operation and maintenance. The oil is sticky, and tar-like at normal temperatures. Due to its pitch-black color and high sulfur content, this oil has a pungent odor. If it gets on clothes, the floor, or the engine, it cannot be removed without washing with diesel. But with that thick oil (HFO), the large marine engine, which is originally a diesel engine (CI engine), runs normally!

To make HFO suitable for combustion in an engine, its viscosity must be reduced significantly, so the oil must be heated to about 100 degrees Celsius before entering the engine. The oil also has to be purified as well to make it suitable for use in engines since HFO has a high water content. These works require a considerable amount of heat energy and for that steam is required. Therefore HFO plant without a heating system is completely inoperable. Every oil tank and pipeline must have a trace heating system.

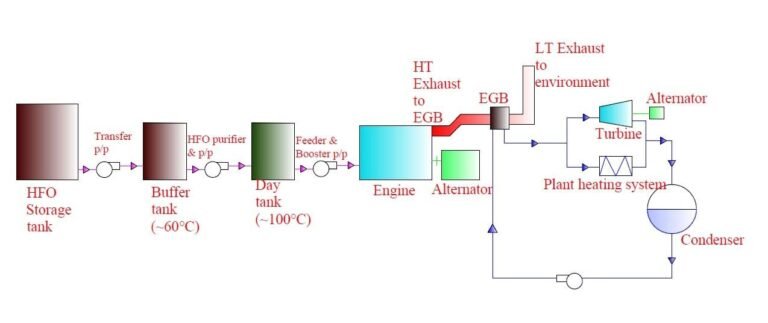

Keeping this need in mind, the idea of using the heat energy of the exhaust gas of the engine has come. Marine engine exhaust temperature is around 450-500 degrees Celsius. At this temperature, the EGB (exhaust gas boiler) can be easily operated, and with the steam produced, the heating system of the entire plant can be run, and the turbine can also be rotated using this steam. In this way, besides HFO heating with the steam produced by using the exhaust temperature of the engine, producing some additional electricity along with the main electricity production by running the turbine is called Cogeneration. Since HFO plants are required to have heating arrangements, EGBs are there in all plants. But unless it is a very big plant, cogeneration with turbines may not be available in all plants.

Here are some examples from where I worked, as engine-based power plants are pretty much the same structure.

-

17 units of Wartsila 18v46 engines and 17 units of ABB AMG 1600 alternators – each Genset has a capacity of 17.076 megawatts. Then a total of 290 megawatts of electricity can be obtained with these 17 engines.

-

1 unit of Alfa Laval EGB with each engine, along with HP, LP steam drum.

-

3 units of Triveni TST 2060 steam turbines and 3 units of TDPS alternators – each Genset of 8-megawatt capacity. Then a total of 24 megawatts of electricity can be obtained with these 3 turbines.

That means the capacity of the entire plant is 314 megawatts. Excluding self-consumption, it is possible to supply approximately 308 megawatts of electricity to the national grid. The 24 megawatts coming from the turbine does not require any additional fuel, only the heat that had to be released to the environment while running the engine is being used. Therefore, utilizing the exhaust heat is always environmentally friendly. Apart from the HFO power plant, EGB and Turbine can also be run with Exhaust gas in a gas engine-powered plant (e.g., United Ashuganj 200-megawatt plant). I am adding a simplified block diagram for easy understanding of the whole system.

In general, there are 3 major departments in a power plant – Operation, Mechanical Maintenance, and Electrical Maintenance. In the UAnPL, there is a cogeneration facility, using the exhaust of the prime-mover of the plant to operate boilers, thus steam generating for heating and operating turbines. As there is cogeneration in the UAnPL, the Operation team is further divided into two teams –the Engine Operation and the Turbine Operation.

As electricity is an emergency national service, power plants need to be in operation 24 hours a day, 365 days a year. The operation team works in shifts, dividing the total 24 hours into 3 shifts. Those who are not used to keeping late hours or early rising, or those who are allergic to highly routined life, may not like the duty of a power plant operation engineer that much. Because shifting duty will hamper one’s biological clock as well as social life! There will be no Friday or Government holiday or even an Eid day for an Operation engineer. Hence, it becomes difficult to attend a family program or a social hang out. “Dost, tomorrow is the weekend, let us go to a movie. It will be great fun!”, an Operation engineer can do nothing but often refuse this type of proposal from a close friend.

However, to repair the biological clock, a power plant operation engineer gets a 3-day off-day at a stretch after completing a 9-day duty cycle. Sometimes, it becomes a 4-day off-day after doing duty for 12 days at a stretch, based on the company policy. These off days are necessary to recover from the fatigue of shifting duty, and enjoyable as well.

On the other hand, the Maintenance team does a regular 9 am to 5 pm duty (unless emergencies occurred in a plant), with one day weekend. However, in some emergency cases, they also need to do shifting duty. A major problem of the Bangladeshi companies is that they do not prefer graduate engineers in the Mechanical Maintenance team, not even the mechanical diplomas, rather they only prefer marine diplomas. We will discuss the reasons in detail in the later part of this writing.

A good practice in power plant duty is to maintain the duty hour. 5 pm means 5 pm here, no need to stay at the plant unnecessarily till 8 pm to show your boss that I am working so long! However, an emergency breakdown may take some extra hours from you. But who does not know, an emergency in an emergency? The incident of National Grid blackouts a few months ago can be mentioned here, though it was an emergency for the Transmission and Distribution department, not for the Generation department.

Extreme physical ability and willingness to utilize it is the primary condition to work in an HFO power plant. If I say it in a negative tone, I need to say this place is a place for the physical laborer. Because you cannot but sweat when you are going to tighten some nuts with 600 Nm torque by your hand standing in a 40-degree Celcius engine hall. Again, opening the engine cylinder’s rocker arm covers to dismantle rocker arms or injectors, you may not need to be a bodybuilder, but the intensity is not too less than that! But if anyone has a passion to do mechanical work by hand, a power plant is his dream place.

A mechanical engineer can find engines, boilers, turbines, cooling towers, pumps, compressors, pipings, fuel treatments, water treatments, fire fighting, HVAC, and whatnot! An electrical engineer can find alternators, automatic voltage regulators (AVR), switchgear, low-medium-high voltage bus bars, transformers, substations, sensors, PLC systems, motors, automation, and whatnot! No other industry is going to offer you so many types of equipment and engineering systems in a place. Therefore, power plant people, especially the private ones become “jack of all trades” within the shortest.

Mentiontioning private with more emphasis has a definite reason. Engineers of private power plants, unlike the government plants, need to do each operation and maintenance job on their hands. There is no luxury of having the job done just by giving orders to the technicians or contractors. From tightening nuts to covering insulation on a hot surface, carrying a heavy motor on the shoulder, replacing parts in scheduled maintenance, cleaning boilers or cooling towers, and final documentation and report generation, all are done by the engineers.

There is a stereotype about corporate jobs among us. That is wearing ironed full-sleeve shirts, black pants, and polished shoes, sitting on a revolving chair in an air-conditioned room, opening a laptop on the desk, and drinking a cup of coffee. This image shall be removed from the brain before starting a job in an HFO power plant. Rather the reality will be wearing a sweaty and oily boiler suit, heavy safety shoes, and a white helmet. Oh well, there will always be some waste fabrics (rags) in the pocket of your boiler suit. If there is any filth or a drop of oil in front of you, you must clean it immediately using the rags. You also have to clean your job place and organize your tools on your own. That responsibility has a cheeky name as well, “Housekeeping”!

Seeing this description in black and white, someone may fantasize, but the reality is harsher than the fantasy. “You are a graduate engineer, why have you come here to die?”, you will face this question a hundred times! You need to blend in with the group of marine diplomas with a smile or be left out. For this situation, I have already told you earlier, almost all private power plants prefer marine diplomas over graduate engineers. Those marine diplomas are trained to do hard work from their academy. Boy, will you be able to wipe the sweat from your cheeks and face as an engineer? Again, the pay structure of the private sector will make you frustrated sometimes. Plants will receive a capacity charge from the government whether it runs or be idle. But your increment, bonus, and other benefits will be cut for little or no reason at all! Profit bonus is a daydream in the private sector, can you bite the ground in these situations? If not, simply leave this sector, you should walk the other way!

I can remember the Covid lockdown time. “Home office” was a new concept introduced among office-going people. At that time in the plant, we were wiping the sweat off our foreheads in the humming of heavy engines. “If we do home office, how will the others run their AC and fan, and watch movies and browse the internet?”, sitting by the Karnaphuli in our rest time, we often laughed out loud, sometimes that laughing sound seemed sadistic!

Reading all of these, someone may feel I was not happy in my power plant tenure! But you know what? Whenever I close my eyes after these years, I can still remember that 23rd of June 2019! I can still feel the breeze by the side of the Karnaphuli, can still hear the sounds of large engines, and can still remember the day when I reached Anwara for the first time! I am not a power plant engineer anymore. But, deep inside me, I can feel the power, the power of a power plant engineer. I can say with a proud voice, “a power plant took birth before my eyes!”

Md. Tanvir Siraj is a mechanical and industrial production engineer as well as a researcher