Mohammad Tanvir Hossain –

The Israel-Palestine conflict is one of the most complicated and divisive issues in the world today, which started as a regional conflict one hundred years ago. a struggle for the same territory between two quite dissimilar parties. It has national, political, geographical, cultural, and religious roots. Israelis and Palestinians both want the same thing: land. To better understand its reasons and underlying issues, let’s retrace the Israeli-Palestinian conflict through a historical journey.

Early History:

The term “Israel” first appeared in an inscription recovered on a stele that was built at Thebes (modern-day Luxor, Egypt) by Merneptah, an ancient Egyptian pharaoh who ruled from roughly 1213 B.C. to 1203 B.C. The inscription refers to a military operation in the Levant (an area that encompasses modern-day Israel, Palestine, Lebanon, Jordan, and Syria) during which Merneptah is said to have “laid waste” to “Israel” along with other kingdoms and towns in the area.

According to the Hebrew Bible, the Jewish people left Egypt more than 3 thousand years ago as refugees and traveled to the Levant before beginning to subjugate the native inhabitants. However, modern academics disagree about whether there is any validity to this biblical tale. While some academics contend that there was no exodus from Egypt, others contend that some Jews may have left the country during the second millennium B.C.

The First Kings:

Based on Hebrew Bible, David (known as Prophet Dawud by the Muslims) became Israel’s first undisputed king after defeating the giant Goliath and his Philistine army. The Hebrew Bible also states that King David oversaw a series of military operations that turned Israel into a strong monarchy with its capital at Jerusalem.

King David’s son Solomon (known as Prophet Suleiman by the Muslims) took over the throne after his father died and built what is now known as the First Temple, purportedly the first temple designed specifically for worshiping God. The Ark of the Covenant (a chest that is supposed to hold tablets bearing the Ten Commandments, engraved by God for Moses or Prophet Musa on Mount Sinai) was housed in this Jerusalem temple.

Northern and Southern Kingdoms:

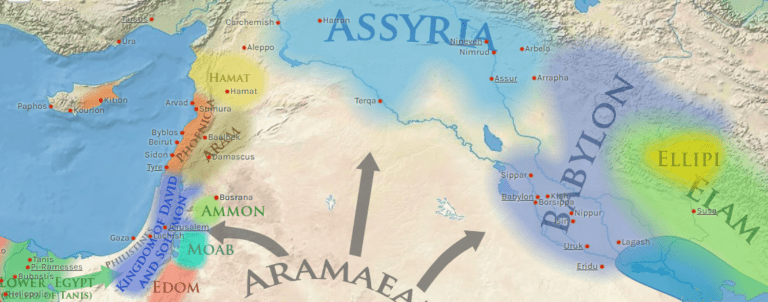

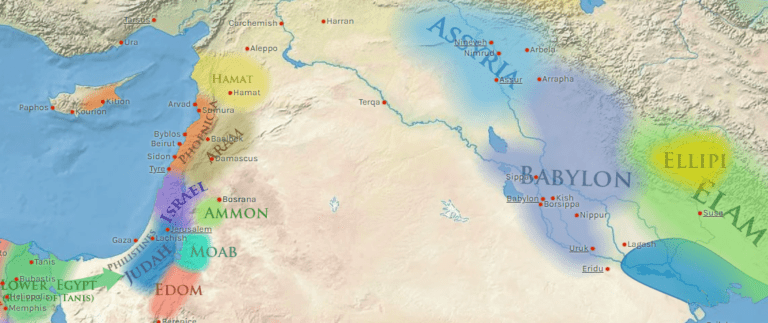

After King Solomon’s passing in around 930 B.C., the kingdom was divided into a southern kingdom called Judah, named for the Judah tribe that ruled the new kingdom, and a northern kingdom, which kept the name Israel. Hebrew Bible implies that disagreements over taxation and corvée labor (free work required for the state) contributed to this breakdown.

Even though they frequently engaged in conflict, Israel and Judah coexisted for almost 200 years. Israel also engaged in conflict with the non-Jewish kingdom of Moab, which was based primarily in present-day Jordan. The Louvre Museum in Paris currently houses a Moabite king’s ninth-century B.C. stele that describes the conflict between Israel and Moab.

The Assyrian Siege:

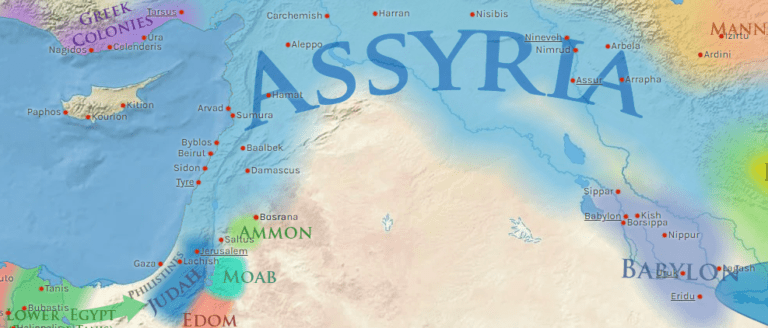

The Assyrian Empire, which originated in present-day northern Iraq, increased in size and conflicted with both Israel and Judah during the ninth and seventh centuries B.C. The Assyrians destroyed the northern kingdom in 722 B.C. and exiled its inhabitants as part of their military strategy (resulting in the so-called Lost Ten Tribes of Israel).

The city of Jerusalem withstood this Assyrian assault under the leadership of Judah king Hezekiah. He built the Siloam Tunnel and Broad Wall, which are still visible today, to help Jerusalem fight the Assyrian siege of Jerusalem in 703 B.C., although he also paid homage to the Assyrians as a vassal state afterward.

Exile by the Babylonians:

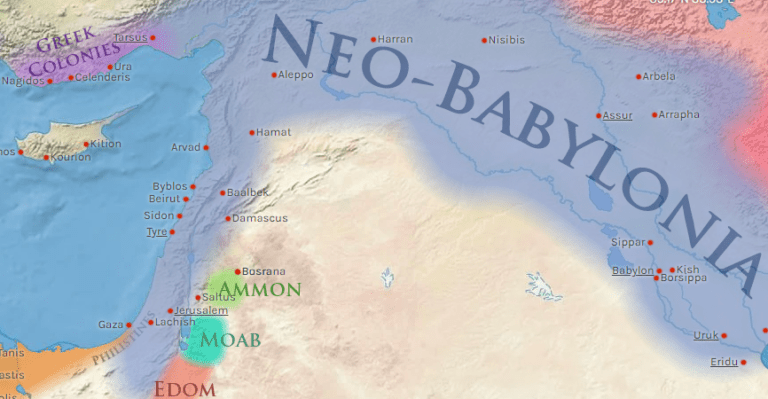

The Assyrian Empire fell in 612 B.C. to a coalition led by the Babylonians and Medes. The Babylonians took the region, sacked Jerusalem, and destroyed the temple in 598 B.C. From 589 to 582 B.C., more Babylonian military operations wiped out the Kingdom of Judah, capturing its most powerful inhabitants and transporting them to Babylon.

Return to the Homeland and Reevaluation of the Religious Beliefs:

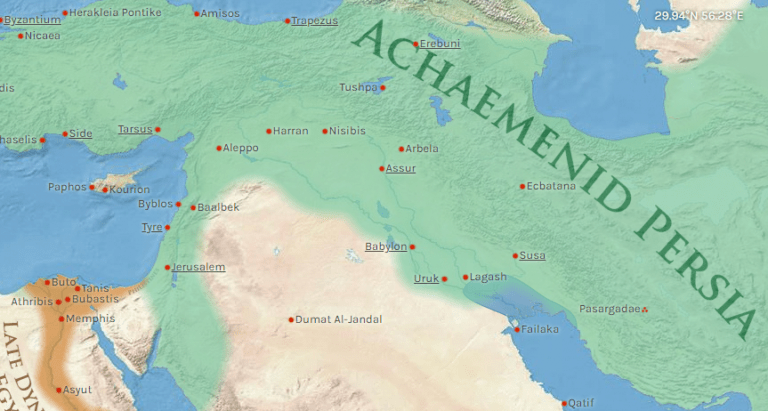

The Achaemenid (Persian) king Cyrus the Great conquered Babylon and freed the Jews to re-enter their own country in about 538 B.C. The exile from a place they believed had been promised to them by God and the destruction of their communities forced the Jewish clergy to reevaluate their religious convictions then. Concluding that they had not worshipped God exclusively, it was a turning point in Israelite religious belief and practice, and, moving forward, it would be characterized by strict monotheism.

A temple was built on Solomon’s destructed temple site giving rise to the Second Temple Period, which encompassed the period between the Jews’ return to their ancestral homeland and the revision of their religious beliefs (roughly 515 B.C. to 70 A.D.).

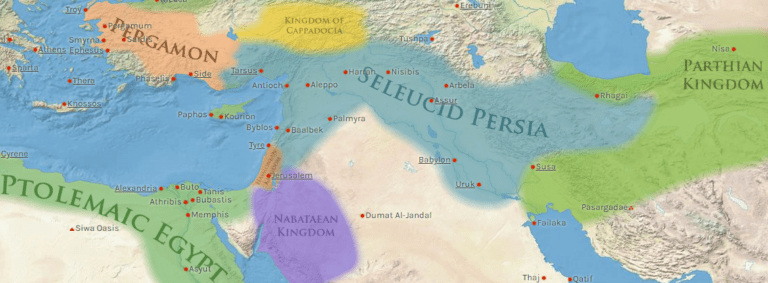

Imposition of Hellenistic Ideas by The Seleucids:

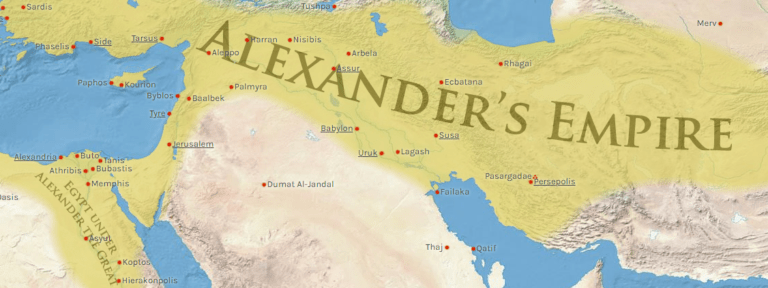

The territory was ruled by the Persian Empire until Alexander the Great’s army seized control of it in 334 B.C. Alexander forced Hellenistic (a form of Ancient Greek religion) cultural norms and ideas on Judea, as he did in every area he conquered, which some Jews adopted and others rejected.

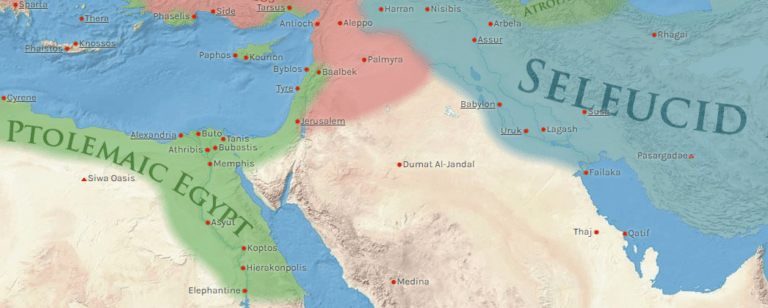

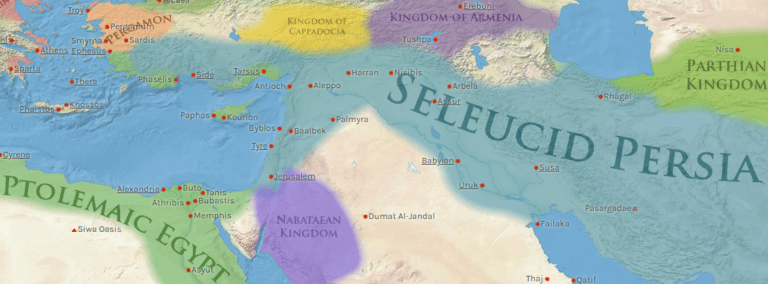

The area once known as the Kingdom of Judah was conquered by Alexander’s general Ptolemy I after his death in 323 B.C. He also ruled Egypt but lost it to the Seleucids of Syria in 198 B.C. The Seleucids controlled the area until the Maccabean Revolt of around 168 B.C. overthrew king Antiochus IV, which resulted in the victory of the Jewish forces and the consecration of the temple (commemorated by the festival of Chanukah).

The Maccabean Revolt and Hasmonean Dynasty:

Although historically understood as a revolt by religious freedom fighters (led by Judas Maccabeus) against foreign occupation and religious oppression, it also started a civil war between Hellenistic Jews and the traditionalists who had rejected Hellenism. Antiochus IV got involved as an ally of the Hellenistic Jews.

Regardless, the Israelites’ triumph against the Seleucids gave them the chance to build the Hasmonean Dynasty (possibly named after Asmoneus, an ancestor of the Maccabees), which would become the last independent Jewish monarchy in the area. The Hasmoneans pursued an expansionist agenda, seizing control of significant trading hubs on their border that had previously belonged to the prosperous Kingdom of Nabatea. These actions put them in regular conflicts with the Nabatean kings.

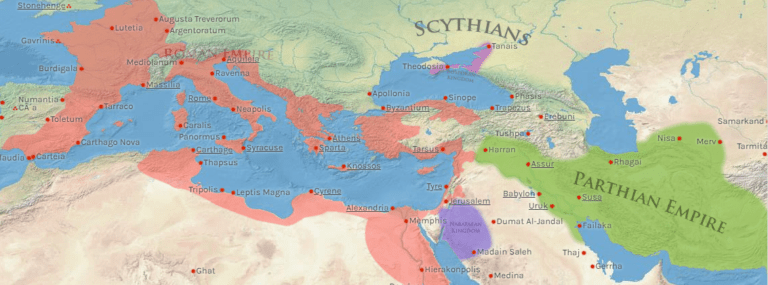

Roman Interference and Fall of the Independent Judea State:

The wealth of the Nabatean Kingdom and the civil wars of the Hasmonean Dynasty attracted the attention of Rome. Roman general Pompey the Great acquired control of Nabatea in 64 B.C. and meddled in Hasmonean affairs in 63 B.C. Even though Hasmonean kings still held the throne, Rome’s intervention marked the end of the independent kingdom. Judea was made a client state of the empire when Rome installed Herod the Great as the ruler.

Revolts and the Destruction of Judea:

The Judean population resisted Roman rule, and tensions eventually exploded in the First Jewish-Roman War (also known as the Great Revolt) in 66–73 A.D. Roman general Titus destroyed Jerusalem and laid siege to the mountain fortress of Masada. Masada’s last line of defense was shattered when the defenders chose to commit suicide rather than give up or be captured. As a result, a huge part of the people dispersed or was sold into slavery, ending the last stand of resistance.

The Second Jewish-Roman War, also known as the Kitos War, occurred between 115 and 117 A.D. It ended in more extensive mass killing and population displacement.

The last and most significant uprising was The Bar-Kochba Revolt (also known as the Third Jewish-Roman War), which took place between 132 and 136 B.C. Emperor Hadrian’s decision to build a new city, Aelia Capitonlina, on the ruins of Jerusalem and to build a temple to the god Jupiter on the Jewish sacred place, the Temple Mount, was the flashpoint of this conflict, even though there were many other variables at play.

The rebellion, led by Simon bar Kochba, was originally successful. He was able to establish his rule and control the area for 3 years before Rome put an end to the uprising. Thousands of people were slaughtered and others scattered. All Jews were banished from the area, and Hadrian prohibited their return under penalty of death.

Throughout the first century A.D., there were unprovoked assaults, riots, and mobs against the Jews scattered around the Roman empire. According to a narrative by the Jewish historian Josephus, 50 thousand Jews were massacred in 66 A.D.

In 70 A.D., the Romans fully reclaimed Jerusalem and demolished the Second Temple with only a portion of the western wall remaining (though recent archeological discoveries date portions of the wall to later periods). The Western Wall remains a sacred site for Jews.

Israel ceased to exist following the destruction of Judea and the ensuing diaspora until the modern State of Israel was established by the UN in 1947–1948 A.D. Through the years, this connection between the ancient Kingdom of Israel and the contemporary state bearing the same name has been fiercely disputed and is still a source of controversy.

[…] Photo: The Balfour Declaration Click to read first part […]

[…] Israel Occupied West Bank Maps Under 1995 Oslo Accords (Photo: Palestinian Academic Society for the Study of International Affairs) Click to read first part […]