Conflict History: World War I (Part 3)

Mohammad Tanvir Hossain –

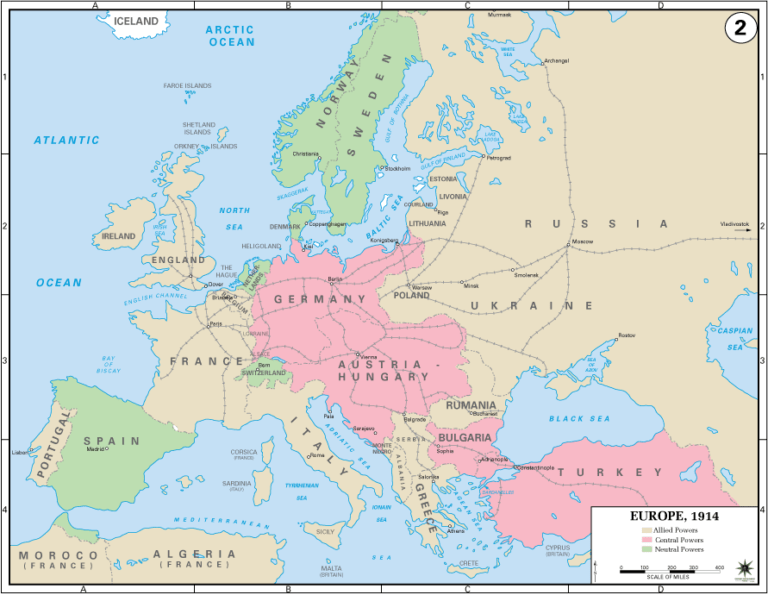

World War I, also known as the Great War, was an international struggle that engulfed more than 100 nations in the world, including the majority of European countries, between 1914 and 1918. The war was fought between the Allies or Entente Powers (primarily France, Great Britain, Russia, Italy, and, from 1917, the United States) and the Central Powers (primarily Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria, and the Ottoman Empire). Officially, Germany was mostly to blame for the war’s four years of unimaginable carnage. But several complex reasons, including a gruesome assassination, contributed to the war.

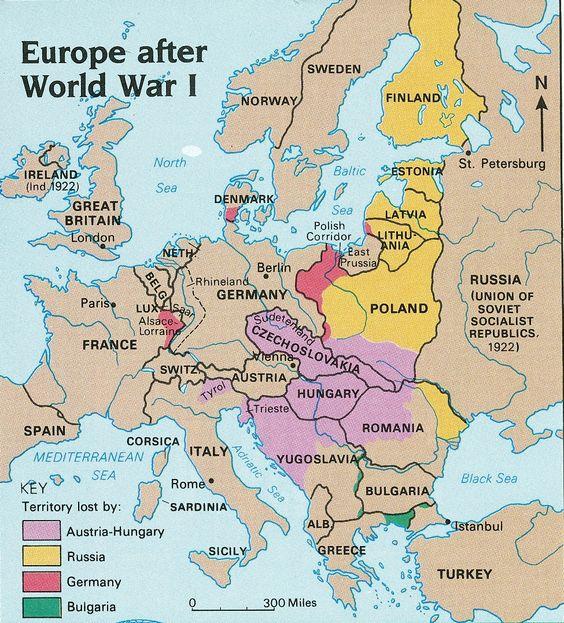

Fall of Empires:

World War I was followed by the fall of empires (Russia in 1917, German and Austro-Hungarian in 1918, and Ottoman in 1922). Austria, Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia, Romania, Poland, Hungary, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Finland, and Turkey were established as independent republics. It also sparked colonial uprisings in the Middle East and Vietnam.

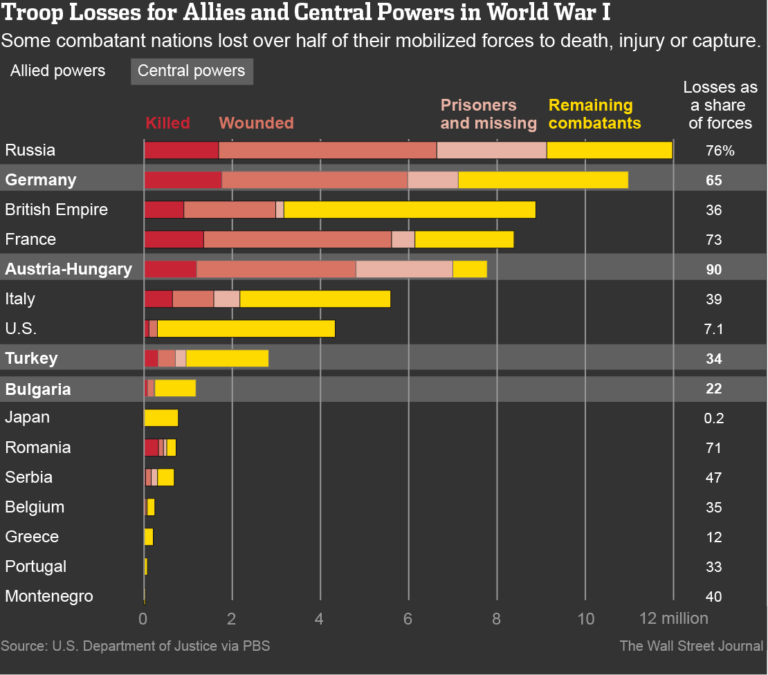

Casualties of World War I:

No other earlier conflict in history caused the loss of more human lives than WWI. Around 4 crore people died in WWI in all, including both military personnel and civilians. 2 crore people died and 2.1 crores were injured. 97 lac military soldiers and almost 1 crore civilians were included in the total number of fatalities.

Spanish Flu Pandemic in 1918-1919:

The outbreak started in 1918, during the closing months of WWI, and historians now think that the war may have contributed to the virus’s spread. Soldiers on the Western Front who lived in close quarters and filthy, wet circumstances grew ill. This was a direct outcome of malnourished people’s reduced immune systems.

In the summer of 1918, as soldiers started to take leave and return home, they brought the virus that had sickened them with them. In the soldiers’ home nations, the virus spread throughout cities, towns, and villages.

One-third of the world’s population, or roughly 50 crore people, are thought to have contracted this virus. At least 5 crore deaths were predicted to occur globally.

The Financial Cost of World War I:

Compared to other wars in history, WWI was the most expensive. Although the whole cost is complicated and may never be fully understood, one estimate places the direct expenses between 125 and 186 billion US dollars and the indirect costs between 151 billion US dollars. Germany spent 45 billion US dollars, followed by Britain and its Empire (47 billion US dollars) and the United States (27 billion US dollars after entering the war in 1917).

Breakdown of Gold Standard and Rise of Inflation:

Gold standard served as an anchor for the value of money as long as it was in place. But when WWI broke out, practically all nations severed their ties to gold. As a result, they were able to raise the money supply without being constrained by the central banks’ gold reserves.

Inflation rose sharply as exchange rates fluctuated against one another. The discount rate did not increase at the same rate as inflation, which boosted the economy of speculation.

In 1917, inflation peaked at 25 percent and 50 percent year over year in the UK and Germany respectively. Before the US entered the war in 1916, growth and inflation both experienced significant accelerations. GDP increased by 14 percent year over year, while inflation peaked in 1917 at 17 percent year over year.

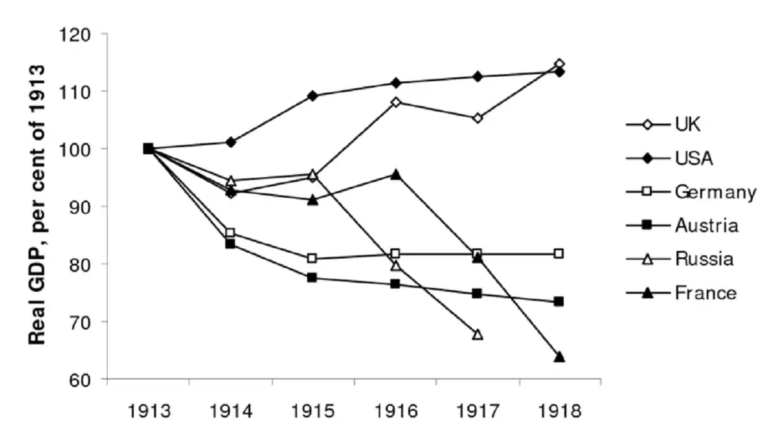

The Economic Loss during World War I:

Although a nation’s economy may benefit from spending during a conflict, the loss of industry might rapidly outweigh this benefit. France was economically devastated while being a member of the successful Allies. The Western Front had been fought solely on French soil, and it had cost a fortune.

Another Allied power, Italy, emerged with an economy that was more powerful but unbalanced, which quickly caused political unrest. A revolution broke out in Russia, a former Allied state that had exited the war in early 1918, largely as a result of its faltering economy.

The only two countries, that significantly improved their economic standing after WW I, were Britain and the United States, both of which were spared fighting on their respective shores.

Despite never being invaded on the Western Front, both Germany and Austria-Hungary experienced economic weariness. The Austro-Hungarian Empire was split into two distinct countries, Austria and Hungary, as a result of economic problems and the cost of the war.

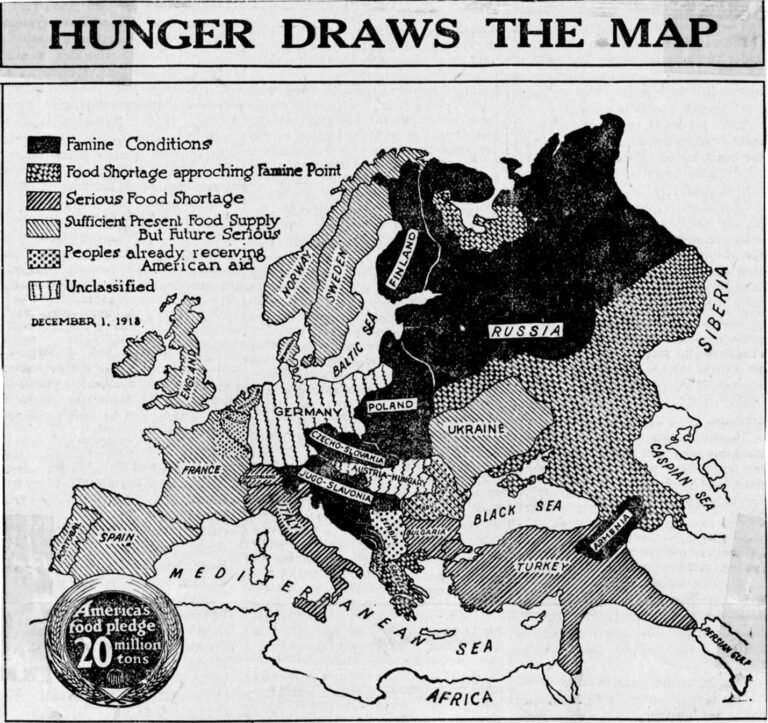

Food Security during World War I:

WWI not only destroyed communities but also completely altered the food culture of North America and Europe. The daily feeding of 75 million men from the Entente and the Central Powers in 1918 posed an unparalleled task to armies.

Despite shortages, food had to be provided for hundreds of millions of civilians who were essential to the war effort. Food was a crucial issue in this all-out conflict since states heavily intervened in food production and distribution to ensure that populations had access to the food they needed to survive. Economic warfare was fought on a worldwide scale, and one of the goals was to cut off the enemy’s food sources.

Food distribution failed in Turkey and Russia. Urban food riots catalyzed the Russian revolution. A large number of people in Turkey died from hunger. Later, Austria-Hungary experienced the same catastrophe.

Germany implemented several government restrictions on food production and distribution, but these proved to be poorly planned and exacerbated the consequences of the British naval blockade. Since 1916, Germans became increasingly malnourished due to substitute diets with low nutritional value.

France, Italy, and especially Britain were supposed to experience the same food crisis as a result of Germany’s campaign of unrestricted submarine warfare. These nations heavily depended on grain imports and saw submarine warfare as a dangerous threat. They made an effort to enhance their food production, but their main success was the introduction of effective rationing mechanisms. Early in 1918, Britain began rationing in London, and by the summer, it had been implemented countrywide. With this state interference, British citizens defied German expectations.

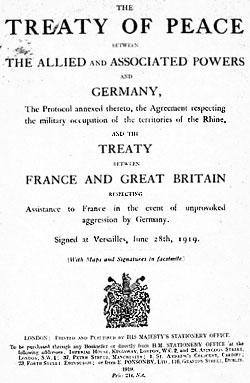

The Treaty of Versailles:

The Treaty of Versailles was signed on 28th June 1919 at the Palace of Versailles in France. This pact was one of many that put an official end to World War I. The terms of peace between Germany and the victorious Allies, led by the United States, France, and the United Kingdom, were laid down in the Treaty of Versailles. Different treaties were negotiated by other Central Powers (most notably Austria-Hungary) with the Allies.

Germany was forced to accept tough peace conditions from the European Allies, including giving up all of its foreign territories and almost 10 percent of its total area. Other significant provisions of the Treaty of Versailles required Germany to hold war crimes trials against Kaiser Wilhelm II and other leaders for their aggression, limited Germany’s army and navy, prohibited it from maintaining an air force and called for the demilitarization and occupation of the Rhineland.

The “war guilt clause” or Article 231 of the treaty, most commonly referred to as the “most significant provision”, required Germany to assume full responsibility for igniting World War I and to make hefty reparations for Allied war losses.

The deal infuriated the Germans, who saw it as a dictated peace and were extremely offended that they were given the sole responsibility for the war. Germany was charged with a reparation fee exceeding 132 billion gold Reichsmarks or almost 33 billion US dollars. Despite the claims of economists at the time that such a significant sum could never be collected without disturbing global finances, the Allies urged that Germany be compelled to pay, and the treaty gave them the right to retaliate if Germany didn’t make its payments on time.

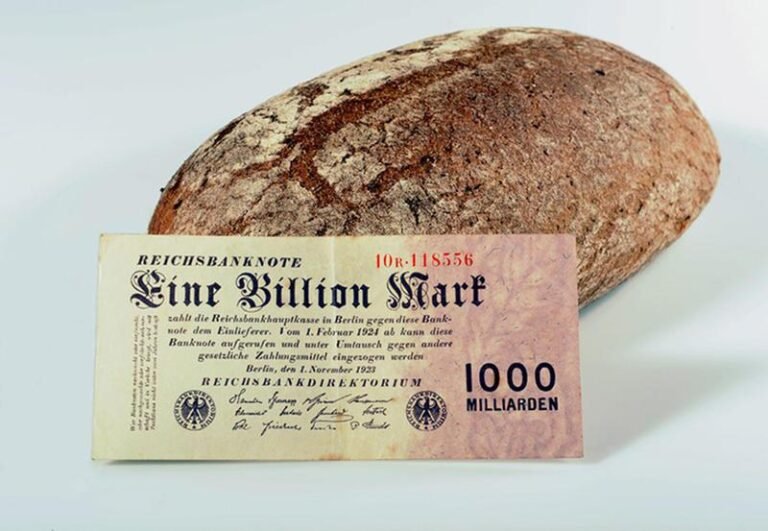

Hyperinflation:

American bankers gave Germany money so that it could pay the Allies’ reparations and settle its debt to the country. In 1923, Germany fell behind on its restitution obligations due to the Allies’ refusal to renegotiate the terms. Its economy further collapsed as manufacturers closed as a result of France and Belgium occupying the industrial Ruhr region to compel German repayment.

Germany intensified its currency printing to pay its debts, which resulted in such hyperinflation that German Mark was essentially worthless. German Marks to US dollars fell from 32.9 to 1 in 1919 to 433 trillion to 1 by 1924, a dramatic decline. German Marks were printed on paper that was more valuable as building materials for kids or kindling.

In 1922, a loaf of bread cost 163 Marks. By September 1923, during hyperinflation, the price hiked up to 1.5 million Marks and at the peak of hyperinflation, in November 1923, a loaf of bread cost 200 billion Marks.

War Debts:

America’s cobelligerents borrowed roughly 10.35 billion US Dollars from the US Treasury during and immediately after WWI. Of that amount, 7.077 billion US dollars constituted cash loans made before the armistice, 2.533 billion US dollars was advanced to support reconstruction after the armistice, and an additional 740 million US dollars represented post-armistice relief supplies and liquidated war inventories.

The US government then borrowed money from its people, mostly through Liberty Bonds with a 5 percent interest rate. The US government agreed to provide the debtor countries a 3-year delay of interest payments during the period of economic disarray in Europe. However, it implied that the borrowers would eventually be expected to pay back the debts. Later, a deal was reached for the principal to be repaid over a period of 62 years with an interest rate of slightly over 2 percent.

However, the governments of the 4 main debtor countries — Great Britain, France, Italy, and Belgium — felt that the American contribution to a shared battle should have been the complete cancellation of the loans. Great Britain, which did not want to lose its status as a creditor country and a financial hub, and the other countries, who did not want to lose access to American capital markets, reached settlements reluctantly.

On 31st December 2006, Britain made a final payment of about 83 million US dollars and thereby discharged the last of its war loans from the US.

Germany made its last debt payment of about 94 million US dollars on 3rd October 2010, the 20th anniversary of German reunification.

The French government agreed in the Mellon–Berenger Accords (20th April 1926) to fund its war debts at the favorable rates offered by the United States. However, it was extremely unpopular in France, whose citizens believed that the US should either link payments to reparations from Germany or waive the debt because of the significant losses in life and property that France had sustained. In the end, following the great economic depression, most of the debt was never repaid.

Hegemonic Transition:

The conflict signaled the beginning of the end of London’s hegemony and the rise of Wall Street (New York) to a position of worldwide supremacy at the pinnacles of the global financial system. By 1919, this transition was far from finished as the largest overall foreign capital stock was still held by Britain.

However, the rapid rise of America’s substantial net creditor position was a clear indication that the British financial hegemony was coming to an end. It became evident during the conflict that the American government was better able to work with its private financial sector and the US Federal Reserve was a more active and potent central bank.

Some other financial centers also emerged in European neutrals, particularly in Stockholm, Zurich, and Amsterdam. The financial fatigue of the larger nations surrounding them greatly benefited these centers. For most of the 1920s, they would punch above their weight while British, French, and German banks fought to rebuild their pre-war standing. They established themselves as appealing conduits of cash for reconstruction.

The Decline of British Dominance:

Britain was the world’s economic superpower before WWI. The nation had tremendous amounts of wealth and resources thanks to its quick rise and extensive empire. However, it was unprepared for the financial effects of the great war.

Even though Britain ultimately won the war, the ramifications would last for many years. An important component of the British economy, foreign trade, had been severely hurt by the conflict. Countries shut off from the British market were compelled to develop their industries, which made them independent of Britain and put them in direct competition with her. Britain would go through its worst economic downturn ever in the years 1920–1921.

An important turning point in the collapse of Britain as a global power was WWI. By the middle of the 20th century, the United States would overtake Britain as the principal economic force in the world.

The United States of America: Inception of A New World Power

The US had the biggest economy in the world by 1913, outpacing both the UK and Germany in terms of national economic output. Its prewar steel production was more than that of France, Germany, and Britain put together, demonstrating its strength.

WWI quickly opened up new markets for American manufacturers and created an economic boom through exports. From 2.4 billion US dollars in 1913 to 6.2 billion US dollars in 1917, the value of all American exports increased. Major Allied nations like Great Britain, France, and Russia received the majority of it, and they raced to get American wheat, cotton, brass, rubber, vehicles, machinery, and hundreds of other raw and finished goods.

After the end of the war, America’s economic boom quickly faded. In the summer of 1918, factories started to scale back their production lines, which resulted in employment losses and fewer prospects for troops who were about to return from war. Due to this, there was a brief recession in 1918–19, followed by a more severe one in 1920–21.

In the long run, the American economy benefited from WWI. The United States was no longer a country on the periphery of the global arena; instead, it was a country with plenty of financial resources that could change from being a global debtor to a creditor. America had demonstrated its ability to finance and field a cutting-edge volunteer military force while fighting the production war.

Great informative article! Hats Off!