Sidratul Mahmud –

Wari-Bateshwar is an ancient archaeological site located in the Narsingdi district of Bangladesh. It originated in the 4th century BC and has been recognized as a key hub of the Mauryan and Gupta empires. It is thought that in ancient times, it was a significant center of Buddhist culture and knowledge.

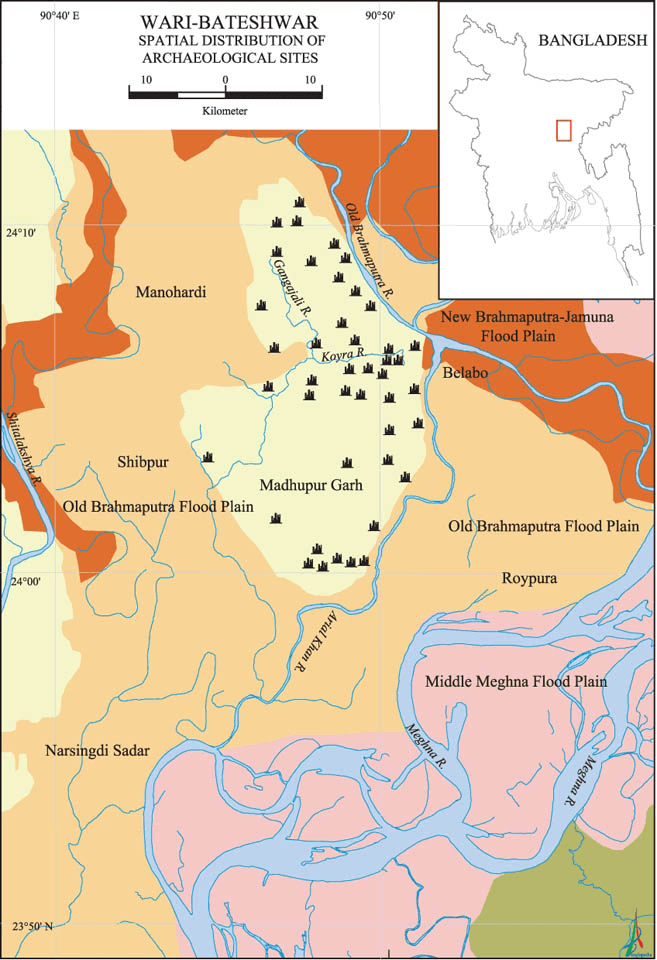

Wari and Bateshwar are two adjacent villages in Amlabo Union under the Belabo police station in Narsingdi. It is located on a remote section of the Pleistocene terrace in Manohardi-Sibpur, which is divided from the Madhupur tract by the Old Brahmaputra and the Laksya rivers.

Wari-Bateshwar is considered one of the most important archaeological sites in South Asia. It was once a prosperous and advanced city of the region, which had extensive trade and cultural connections with other parts of the world.

The Silk Way, which was a prehistoric trading route, is believed to connect Wari-Bateshwar to the ancient Roman and Egyptian civilizations. The discovery of a rolling pot, a type of wired or bronze pottery from the Mediterranean, at the site confirms that trading was a common practice at the time. Wari-Bateshwar may have had contact with Southeast Asia and the Roman Empire, according to Professor Dilip Kumar Chakrabarti of the South Asian Archeology Department at Cambridge University.

It is a fascinating tale of how Wari-Bateshwar was discovered. Digging uncovered numerous archaeological items in the nearby villages of Wari and Bateshwar. Some local archaeologists in the Wari village uncovered a pot full of ancient coins in the unexplored Wari-Bateshwar grounds in 1933. The coins date from 450 BC to 300 BC. Hanif Pathan, a local teacher, gathered 20 to 30 of the antiquated coins there. He then informed his son Habibullah Pathan of the occurrence.

The Archaeological Department of East Pakistan started a systematic excavation in the 1950s. Two antique metal objects were left behind by some miners in the town of Bateshwar in 1955. These goods were displayed to his father by Habibullah Pathan. Then, in Wari-Bateshwar, a long-lost underground storage for silver coins was found in 1956 while digging. Habibullahh Pathan gathered numerous artifacts from Wari-Bateshwar in 1976 and donated them to the Dhaka National Museum.

A digging expedition in Wari-Bateshwar was started in 2000 under the authority of Professor Sufi Mostafizur Rahman, an archaeologist from Jahangir Nagar University. Ancient roadways, dwellings, terracotta, silver coins, hand-crafted metal objects, printed money, weaponry, and a variety of other relics have all been found.

The excavations at Wari-Bateshwar have revealed the remains of an ancient city that was home to a thriving community. It was a period between the 6th and 4th centuries BCE in the modern Magadha, Kashi, Kosala, and archaeological burg. It is thought that Wari-Bateshwar served as the state’s capital, according to Dilip Kumar Chakraborti, a professor at the Department of South Asian Archeology at the University of Cambridge.

Wari-Bateshwar was associated with the Silk Road, an early trade route. Trade was a common practice at that period, as evidenced by the discovery of a rolled pot, a type of Mediterranean, wired, or bronze pottery. Wari-Bateshwar is believed to have had contact with both the Roman Empire and Southeast Asia, according to Professor Dilip Kumar Chakraborti.

The excavation at the site has revealed evidence of a highly developed urban society. Investigations revealed the remains of two fortified regions, which we will refer to as the outer and inner forts from now on. Both fortifications are slowly disintegrating as a result of both natural and human actions. The outer fort, also known as Asam Rajar Garh, is situated in Bateshwar.

At present, it is found at up to 4.87 meters in height and an average breadth of 35 meters at the base. According to the locals, a Koch king and an Assamese king sought sanctuary here in the late 16th to early 17th century AD and constructed the rampart as a barrier from the aggressive advance of both the Mughals and the Pathans.

Two mud ramparts built on the fort’s south and west sides enable it to surround a sizable area. The Rivers Koira Khal and Ariyal Khan, respectively, form the northern and eastern boundaries of the fort. The 3.5-kilometer-long southern rampart of the fort terminates at the River Ariyal Khan. The rampart is intersected by the 138-meter-wide Dangir Beel and the 42-meter-wide Bada Baidyar Beel, respectively, around 2 and 3 kilometers from the southwest corner of the fort. The Koira Khal marks the end of the western rampart, which is around 1.7 kilometers long. A kilometer or so from the southwest corner of the fort, the Chrgachiya Beel, which has a width of 130 meters, crosses the rampart. The rampart’s final section enters Sonarutala village.

The Wari settlement is completely encircled by the inner fort, which is surrounded by four earthen ramparts. The eastern and western ramparts are 518 meters long, while the northern and southern ramparts are 645 meters long. At the base, the width is 16.5 meters on average. The exterior of the fort is surrounded by a canal that is 30 meters wide, acting as a moat. During the wet seasons, it has flowing water, but during the dry seasons, it becomes dry. The fortified area’s remnants show that the location served as an administrative hub.

Professor Sufi Mostafizur Rahman revealed further structural remnants in 2004. The road is a compacted area of 180 meters by 5 meters in size. The next year, he revealed a second compacted section that led away from the 180-meter-long area perpendicularly. He named this discovery an “aby-lane”.

Four trenches were dug during the excavation in 2006 in the west, northwest, and south of the 180-meter-long region. Following all these examinations, two compacted brick grit sections were discovered; each was 10 centimeters thick, and their higher levels appeared to be connected to the 180-meter-long area.

It appears from all the examinations done so far that Professor Rahman was mistaken to read the compacted area as a road and a by-lane. The area might have been a public area in the shape of an outside floor that covered a sizable portion of the southeast corner of the inner fort. When the initial (lower) level had weathered away, the upper level might have been required. Potsherds and beads discovered on the upper floor imply that the outside public area may have also served as a trading hub, much like the hats still visible in rural Bangladesh today.

50 archeological sites have so far been found in and around the Wari-Bateshwar fort city, which is situated by the Old Brahmaputra River. The layout of the archaeological sites makes it clear that the early inhabitants built their towns in areas that were not prone to flooding. This further demonstrates the ancient settlers’ high level of intelligence and their familiarity with sophisticated town layouts. Similar habitation patterns can be seen at Mahasthangarh (Pundranagar).

Ancient Wari-Bateshwar residents were conversant with advanced technical knowledge. They could make beads by cutting the stone. During excavation, raw materials, chips, and flakes used to make semi-precious stone beads were found. They were able to embellish the beads by employing various chemicals. They might also use various chemicals to coat the polished black pottery from the north. High-tech equipment was employed to regulate the temperature while making ceramics.

They were aware of the metal melting process used to make coins. Two different kinds of silver punch-marked coins have been found in Wari-Bateshwar. Coins with pre-Mauryan silver punch marks, such as Janapada, are one type. From roughly 600 BC to 400 BC, Janapada coins were in use in the subcontinent. The discovery of Janapada coins dates Wari-Bateshwar to the Sodosha Maha Janapada empire of the Indian subcontinent, which existed between 600 and 400 BC.

Ancient Wari-Bateshwar residents were also conversant with advanced technical knowledge. They could make beads and were aware of how iron was processed. The existence of the Wari-Bateshwar fort-city and the Asom Rajar Garh demonstrates the proficiency in the geometry of the locals. These elements demonstrate the ancient people’s intimate familiarity with technology and scientific knowledge, as well as their artistic sensibility, admiration of beauty, and aptitude for various technological activities.

River’s existence suggests that Wari-Bateshwar was a riverport and a major trading hub. Agate, quartz, jasper, carnelian, amethyst, chalcedony, and other semi-precious stone beads were discovered. According to Dilip Kumar Chakraborti, Wari-Bateshwar may be the trading hub Ptolemy (a second-century geographer) referred to as Souanagoura.

Wari-Bateshwar has been recognized as a site of national importance by the Bangladesh government, and efforts are underway to preserve and promote the site as a tourist destination. You can take a bus or train from Dhaka to Narsingdi. The distance between Dhaka and Narsingdi is around 50 kilometers, and the journey takes around 1 to 2 hours depending on traffic conditions. From Narsingdi, you can take a taxi or a CNG (auto-rickshaw) to reach the archaeological site, which is 30 kilometers away from Narshingdi town.

Once you reach Wari-Bateshwar, you can explore the site on foot. There are many temples, stupas, and other archaeological sites to visit at the site, which is spread out over a wide region. The old marketplace’s ruins, which were once a thriving hub of trade and business, can be seen here. Archaeological digs have found a variety of objects, including pottery, jewelry, and coinage. It is thought that the marketplace served as a center for the interchange of goods and services.

There is a museum here that houses a collection of relics and exhibits for anyone interested in learning more about the history and culture of Wari-Bateshwar. Visitors can view artifacts like pottery, jewelry, and tools that were used thousands of years ago at the museum, which offers insightful information about the lifestyles of those who lived in the ancient city.

Wari-Bateshwar is also home to a lot of natural features in addition to the archaeological sites. The area where the site is situated is noted for its extensive biodiversity and is part of the Brahmaputra-Meghna River basin. Visitors can go on a boat tour of the local wetlands, which are home to many different kinds of birds.