Anjum Anam –

The Chakma people are the largest ethnic tribe in Bangladesh. They also call themselves Sangma. They are concentrated in the central and northern parts of the Chattogram Hill Tracts where they live amidst several other ethnic tribes.

Based on the 2022 consensus, the total Chakma population was 483,299, which was 29.29 percent of the total ethnic population in Bangladesh. Over 90 percent of them are concentrated in Rangamati and Khagrachari districts. About 100,000 Chakma people also live in India, particularly in the states of Arunachal, Mizoram, and Tripura. Small groups have settled in other countries as well.

Early History:

There are two schools of thought among scholars regarding the early history of the Chakma people. Both believe that they immigrated to their current homeland from somewhere else.

The most convincing opinion links the Chakma people as having their roots in the former Arakan kingdom, which is now known as modern-day Myanmar. The Chakma are thought to have descended from the ancient Tibeto-Burman group of people who migrated from the Tibetan plateau to Arakan around 2,000 years ago. As the Burmese invaded the Arakan kingdom in the 15th century, the Chakma were forced to retreat to the Chattogram Hill Tract region’s hills and jungles.

The other opinion, which lacks historical evidence, assumes that the Chakma people are Kshatriyas from Northern India. They invaded Arakan towards the end of the 14th century, settled there, and intermarried with the local people.

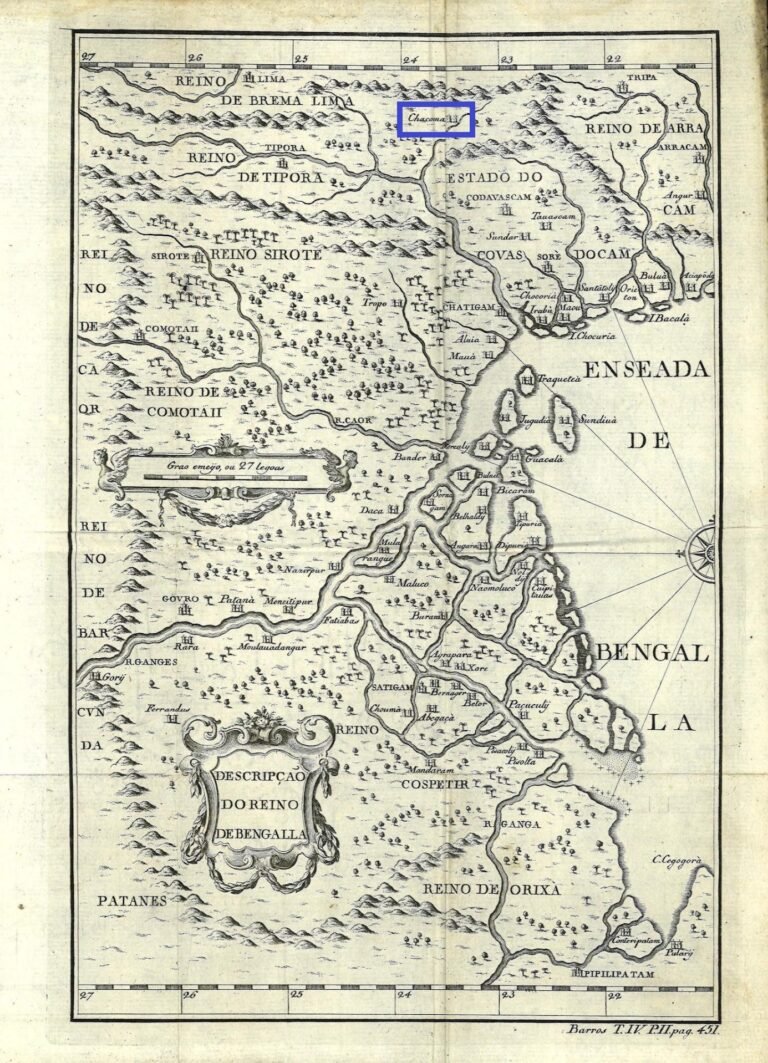

Their early existence has been confirmed with Portuguese explorer João de Barros’ map which depicts “Chacomas” on the eastern side of the Karnafuli River. Although the information for this map originates from roughly 1525 to 1550, the first publication of it is from 1615.

Middle Age History:

In the early 16th century, the Chakma kingdom came under the influence of the Mughal Empire, which had conquered much of present-day India and Bangladesh. After years of conflicts, the Chakma king, Raja Sukhdev Roy, developed a stable relationship with the Mughals in 1713 and agreed to pay tribute to the Mughal emperor in exchange for the right to conduct trade and commerce with the adjoining areas. Despite paying tributes, the Chakma people were practically enjoying independence during that period as the Mughals were focusing on the plains only.

During the British colonial period, the Chakma people came under British rule, along with the rest of present-day Bangladesh and India. The British invasion of the Chattogram Hill Tracts in 1777 sparked a lengthy conflict between the East India Company and the Chakma kingdom. The conflict finally ended after a peace pact was concluded in 1787. In exchange for autonomy in controlling Chakma land, Raja Jan Baksh Khan swore allegiance to the British.

Modern History:

The British government divided the Chittagong Hill Tracts into Chakma Circle, Bohmong Circle, and Mong Circle in 1881, from which Chakma Circle was headed by the Chakma king. Later the government enacted Chittagong Hill Tracts Regulation 1900, and the Government of India Act 1935 to designate the hill tracts as an “Excluded Area” to stop mainlanders from taking ownership of the tribal land.

The Chakma people started asking for their independent state during the Indian national movement in the 1930s. Local British officials promised the tribes that the Chattogram Hill Tracts would be divided up independently in the event of Indian independence to maintain Chakma loyalty in the face of Japanese advances during World War II.

During the partition of India in 1947, the British did not keep their promise to the tribes. Rather, they made the region a part of Pakistan despite the more than 97 percent non-Muslim population there.

Things started well in the Pakistan period which continued the British ways. The 1956 Pakistani Constitution even preserved the status quo by designating the Chattogram Hill Tracts as an “Excluded Area”.

After the Pakistani military ousted the democratic government in 1958 and renamed the protected territory “Tribal Area”, the 1962 Constitution was changed to abolish the prior designation, opening up the admission of all non-tribal people to the Chattogram Hill Tracts.

In addition, the construction of the Kaptai Dam and the creation of Kaptai Lake in the 1960s, as a part of a hydroelectric project, submerged more than 54,000 acres of farmland (40% of arable Chakma land) and displaced over 100,000 people (mostly the Chakma), including the Chakma Raja himself, from their homes. This led to the great exodus (Bara Parang, in Chakma language) which saw people settle elsewhere in the district, including reserved forest areas.

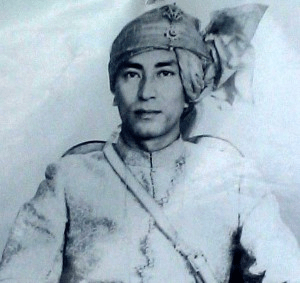

During the 1971 liberation war, 50th Chakma Raja Tridiv Roy declined to join the Bangladeshi freedom fight and sided with Pakistan as General Yahya Khan assured him about autonomy in the Chittagong Hill Tracts region.

After Bangladesh becomes independent in 1971, Raja Tridiv Roy fled to Pakistan where he resided for the rest of his life. He gave his son, Debashish Roy, the throne as the Chakma Raja. Then he devoted 4 decades to serving Pakistan including arguing in United Nations against Bangladesh’s admission into the world body in 1972.

Following the independence of Bangladesh in 1971, Chakma politician Manabendra Narayan Larma established the Parbatya Chattagram Jana Samhati Samiti (PCJSS) on 15th February 1972 to represent all of the tribal populations in the Chittagong Hill Tracts with 4 basic demands –

Autonomy for the Chittagong Hill Tracts, together with provisions for a separate legislative body.

Retention of Chittagong Hill Tracts Regulation 1900.

Continuation of the offices of the traditional tribal chiefs

A ban on the influx of non-tribals into the area.

These demands were turned down, and the Chittagong Hill Tracts were not granted any special status under the Bangladeshi Constitution of 1972. Rather the government continued with the earlier policy of settling poor Bengali people in the hill tracts.

As per article 36 of the Bangladesh Constitution – “Subject to any reasonable restrictions imposed by the law in the public interest, every citizen shall have the right to move freely throughout Bangladesh, to reside and settle in any place therein” – Bangladesh government decided in 1979 to settle 30,000 Bengali families with 5 acres of land, 3,600 takas in cash to each family. By 1984, 400,000 Bengali families settled in the hill tract area. To the dismay of the ethnic people, this started to alter the demographic distribution permanently.

Table: Bengali and Hill peoples Population of the CHT from 1872 to 2022

Year | Total Population | Bengali | Ethnic People |

1872 | 63,054 | 1% | 99% |

1901 | 124,726 | 7% | 93% |

1911 | 153,830 | 8% | 92% |

1931 | 212,922 | 11% | 89% |

1941 | 247,253 | 6% | 94% |

1951 | 287,688 | 9% | 91% |

1961 | 385,079 | 13% | 87% |

1974 | 508,199 | 19% | 81% |

1981 | 745,000 | 39% | 61% |

1991 | 974,445 | 49% | 51% |

2001 | 1,331,966 | 55% | 45% |

2011 | 1,598,231 | 47% | 53% |

2022 | 1,841,829 | 50% | 50% |

In response to these developments, the Shanti Bahini (Peace Force) was formed as the military wing of PCJSS in 1973. It fought against Bengali settlers’ encroachment and promoted its rights. After starting peacefully, the group eventually turned to violence to further its goals.

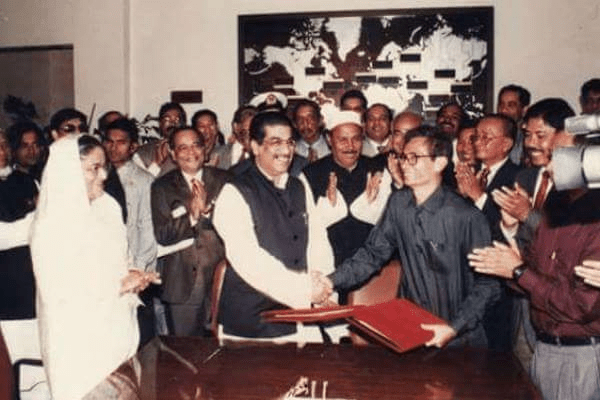

The government’s response to the Shanti Bahini was aggressive, and the army and paramilitary troops were stationed there. There was a lot of bloodshed and violations of human rights as a result of the battle between the Shanti Bahini and the government troops. Official figures indicate that more than 8,500 rebels, soldiers, and civilians were killed during two decades of insurgency. Finally, a peace accord was signed on 2nd December 1997 between the Bangladesh government and PCJSS to put an end to this bloodshed over decades.

Lifestyle:

The Chakma way of life has historically been strongly associated with hill farming or shifting cultivation (JUM in Chakma and JHUM in Bengali). In their settled villages, they would farm the nearby hills’ plots for a while before leaving them fallow to recover organically. Moreover, they farmed land in river valleys. They possessed a sophisticated system of land rights that was far different from what was found in the plains.

Early observers reported that cultivators in the Chattogram hills had a comparatively high standard of living. Vegetables, rice, and cotton were among the significant crops.

Throughout the colonial era, social stratification increased as an elite class formed based on academic accomplishments. Hill farming became increasingly difficult in the 20th century as fallow seasons had to be reduced due to population increase. Hence, more Chakma people had to pursue non-agricultural employment.

Kin Groups and Descent:

The fundamental pillar of Chakma society is the PARIBAR, or family. The next largest unit after the family and homestead is a multihousehold compound, whose members can organize working groups and lend a hand to one another in different ways. Then there are the Hamlets, which are settlements of houses.

For jobs that require travel, such as swidden cultivation, fishing, and collecting, they establish work groups. A leader known as the KARBARI organizes and controls Hamlet’s populace. The village is the next larger group that arranges a few rituals together.

The Chakma people practice patrilineal descent. When a woman marries, she cedes control of her own family and joins her husband’s. Property is passed down through the male line. Despite the patrilineality, maternal kin is acknowledged to some extent. For instance, a person’s cremation ceremony will include members of his or her mother’s family.

Marriage:

Although less frequent today than in the past, polygamous unions are nevertheless permitted among the Chakma. Typically, parents arrange marriages, but partners’ preferences are taken into account. If a boy and girl fall in love and decide to get married, the parents typically agree as long as the marriage law permits it. Exogamic Chakma regulations prohibit marriages between members of the same GUTTI or GUSTHI.

Religion:

The majority of Chakma people in Bangladesh are Buddhists, making them the country’s largest group of followers of the religion. They incorporate earlier religious traditions, such as the veneration of natural forces, with their practice of Buddhism.

The majority of Chakma villages have Buddhist temples (KAANG). Bhikkhu is the Buddhist term for priest or monk, who presides over religious celebrations and rituals.

Rites of Passage:

After the birth of a child, the father builds a fire on some earth that is placed near the birthing bed. This is kept burning for 5 days. The mother and kid are then bathed after the earth has been removed from the scene. A woman is prohibited from cooking for a month after giving birth because she is seen as unclean.

The dead of the Chakma is cremated. The deceased’s body is cleaned, dressed, and placed on a bamboo platform. Cremations typically take place in the afternoon.

Chakma people believe in reincarnation. This indicates that they think the departed person’s spirit will manifest itself as another living being when they pass away. Relatives go to the cremation site the morning following the cremation to look for footprints. They think the deceased will have left behind some evidence of their new incarnation (living form). A few bone fragments are gathered, placed in an earthen pot, and thrown into a nearby river.

The family experiences 7 days of grieving. At this time, no fish or animal flesh is consumed. The last ceremony (SATDINYA), which lasts seven days, is performed. Buddhist monks give religious sermons, donations are presented to the monks, and the entire community partakes in a communal feast during this time. The family also offers food to their ancestors.

Language:

The language used by the Chakma people sets them apart from neighboring ethnic groups. While there are hints that the Chakma people once spoke a Tibeto-Burman language, they currently speak Indo-European. It shares a framework with Chittagonian Bengali but differs from it in terms of the lexicon.

The majority of the Chakma population are bilingual and speak Chakma and Bengali; many also understand other local tongues. The Chakma script is a Brahmic script used to write the Chakma language. But it is not used very often; instead, Bengali letters are used to write Chakma.

Literature:

Chakma literature has a vast canvas with its wide array of genres, including poetry, epic, folktales, myths, dramas, songs, hymns, puzzles, etc. A distinctive element of Chakma literature is the use of proverbs and conventional sayings. These proverbs mostly discuss farming, pets, birds, the natural world, human anatomy mysteries, society, and religion. These proverbs are known as DAGWA KADHA in the Chakma language.

Chakma literature contains several epics. CHATIGA CHARA is the primary work of epic poetry. It contains a description of their journey to Chattogram. It is comparable to Vergil’s “Aeneid”.

Another folktale is TANABEE. It is a lullaby that moms sing to their children to get them to sleep. It provides a thorough account of Tanabee’s beauty and her sorrows that will touch every reader’s heart. It resembles the Bengali folktales “Rupban” and “Komola Sundori”.

Another epic called RADHAMOHAN AND DHANAPATI is thematically similar to “Romeo and Juliet” by Shakespeare. Similar to Romeo and Juliet’s families, Radhamohon and Dhanapati’s families are at odds over their love affair.

Dance and Music:

The Chakma people have their traditional music and dance. They conduct dances during social gatherings and on special occasions.

The HENGORONG, SINGHA, DHUDHUK, and other traditional musical instruments are used by the Chakma people.

Selected people sing the Chakma traditional ballads known as GEINGKHULI, which chronicle the history of the Chakma people. There are specific GEINGKHULI songs for specific occasions, and a GEINGKHULI performance is tailored to the occasion. A GEINGKHULI performance might easily go for days, but it often lasts from dusk to dawn.

There is also a religious song called GOJENA LAMA that sounds a lot like the Muslim hymn Hamd. Every young person sings UVAGEETA, or “Song of the Youth”, which is another genre of song.

Games and Sports:

The Chakma people participate in a variety of traditional sports and games, particularly during the festivals. These games are played by both men and women and frequently, the men compete against the women. The majority of games/sports are team-based, including GUDU-HARA, GHILE-HARA, PUTTI-HARA, POWR-HARA, DOLA-HARA, and DUURI-TANA-TANI, but some are individual, including BODA-BUDI, NHADENG-HARA, HUROH-JUDDHO, and SARHA-HARA.

SHAMUK-HARA and BHOGK-HARA, commonly known as DOLA-HARA, are two examples of indoor games. In addition to the games mentioned above, the Chakma kids also enjoy playing a variety of classic kid games including HATTOL-TANA-TANI, HOBHA-JHANG, and others.

Dress Pattern:

Chakma women wear an ankle-length cloth around the waist which is called a PINON. To be referred to as a PINON, a piece of clothing must feature a SAABUGIH, which is a complex pattern that runs the length when worn. In addition, they cover their waists with a HAADI, a garment with a far more complex pattern. Traditional silver jewelry is also worn by Chakma ladies.

Weaving and Craftsmanship:

Chakma men are skilled artisans who make their daily necessities primarily from bamboo and occasionally from wood. A variety of household products, including TOLOI (mat), BAREING, HALLWONG, AHRI (various sorts of baskets), MEZANG, HUROH-BAH, ODHOK, LUDHUNG, and many more, are constructed from thin, long slices of bamboo known as BETH. The majority of traditional Chakma homes are constructed from bamboo.

Chakma women are skilled weavers and talented designers who make their traditional clothing on the BEIN handloom, a Chakma traditional craft. The components that make up traditional Chakma handlooms are together referred to as SOZPODOR. The Chakma ladies often create a variety of elaborate patterns on a piece of cloth known as AALAM. Next, using this as a guide, designs from the AALAM are blended, mingled, and matched to produce stunning patterns on their traditional clothing.

Cuisine:

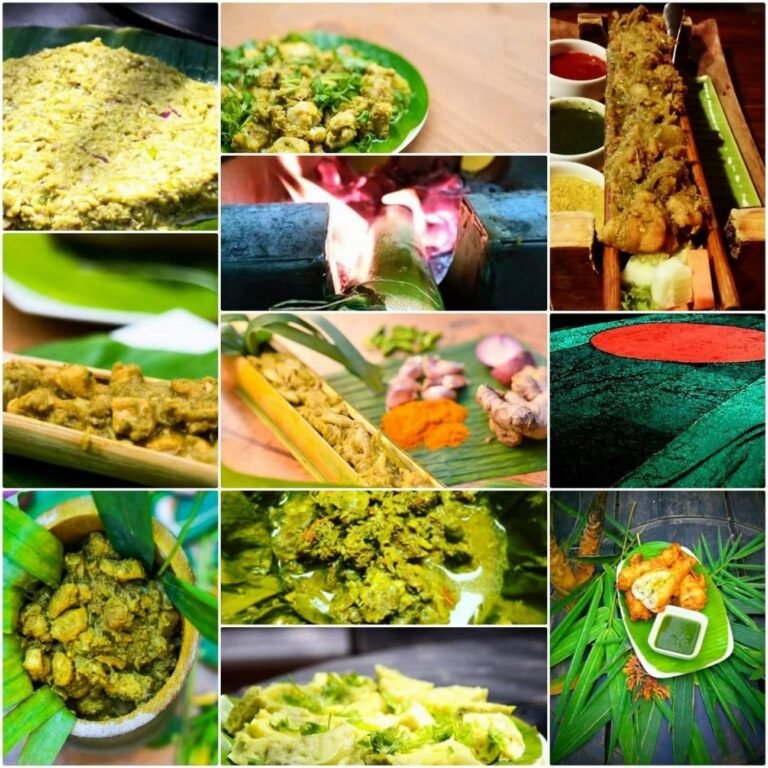

Chakma people employ various traditional methods of cooking including GORAN (cooked slowly in a bamboo internodal tube on embers), PEBANG (cooked on leaves on red embers), PUJCHYA (roasted), and GUDIYE (cooked and ground in a bamboo internodal tube), HORBO (raw vegetables mixed in chili paste). The CIDOL, a fish and shrimp paste with a strong aroma, is a crucial component of Chakma cuisine. Almost all vegetable meals include this CIDOL.

The traditional cuisine also includes bamboo shoots (Bhacchuri). In place of spices, fresh herbs are frequently used in Chakma cuisine. These herbs can be used as a garnish or as a flavoring.

The Chakma people eat rice as their main cuisine, with millet, corn (maize), vegetables, and mustard as supplements. There are yams, pumpkins, melons, and cucumbers among the vegetables. The diet can include fruits and vegetables that have been collected from the forest. Although many Buddhists are vegetarians, fish, fowl, and meat are also consumed.

The Chakma people produce HANJI and JOGORAH, their traditional rice beer. To further purify the alcohol, this can be further distilled (often twice, called DWO-CHUNI) using conventional distillation techniques and tools. During the BIJHU and other significant occasions, alcohol is served.

Main Festivals:

BIJHU – is celebrated in the month of April and coincides with the Bengali New Year. 3 days are dedicated to celebrating BIJHU: PHOOL BIJHU, MOOL BIJHU, and GOJYA-POJYA DIN. BIJHU welcomes the new year and bids adieu to the previous one. Throughout the celebration, the Chakma people visit one another and exchange good wishes for the coming year. On this occasion, the Chakma people serve a special dish called PAAJON-TWON, which has to be made with at least seven different types of vegetables. Rice cakes of many varieties are also made. On this occasion, rice beer is also brewed and served to the guests.

Buddha Purnima – is the most important religious festival of the Buddhists and commemorates the birth, enlightenment, and death of the Buddha. It is also known as Vesak Day. The Chakma people congregate at the temples on this auspicious occasion to offer prayers and offerings to the monks and to hear Dhamma discourses. They stage plays about the life of the Buddha at night. Apart from this, other practices such as lighting thousands of lamps and releasing Phanush Batti (an auspicious lamp made of paper in the form of a balloon) are also done. It is observed on the full moon day of the month of Vaisakha (usually in May).