Providing Safe Water to All: Where We Are

Digbijoy Dey-

Water crisis in Bangladesh! Are you kidding? Bangladesh is home to a network of hundreds of rivers and canals. The world’s largest river delta, the Ganges Delta is here. The country has always been rich in water. Thus, the water crisis sounds weird in Bangladesh.

Crisis can be of different types. Too much water or too little water – both can be considered a crisis. Even the optimum amount of water can cause a crisis if the quality of the water is not good. So, avoiding the water crisis means 1) preventing ‘too much water’, 2) ensuring ‘enough’ water, and 3) ensuring ‘adequate quality’ water (Bangladesh Delta Plan 2100).

Water has different types of use. The first one is of course drinking. Then there are other household purposes such as cleaning, bathing, washing etc. But there are other important uses which include agricultural (for irrigation and livestock mainly), industrial, power generation (hydroelectricity) etc. But in this article, we are going to discuss drinking water only.

The disbelief I stated at the beginning of this article is true for drinking water also. Bangladesh is a land of water, still, water becomes a critical issue here. For drinking water sub-set situation is even more serious. To date, 98 percent of the Bangladeshi population is under basic water coverage. However, there is a vast difference between coverage and quality of water available. Now the question is what ‘basic water coverage’ is.

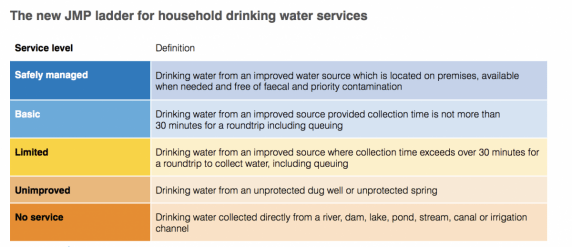

According to WHO/UNICEF Joint Monitoring Program (JMP), basic water coverage is ‘drinking water from an improved source, provided collection time is not more than 30 minutes for a roundtrip including queuing’. Now you can ask, what is an improved source? JMP has tried to categorize improved sources. Improved drinking water sources are those that have the potential to deliver safe water by nature of their design and construction, and include: piped water, boreholes or tubewells, protected dug wells, protected springs, rainwater, and packaged or delivered water. Sounds good, no? Because that means 98 percent of the Bangladeshi population has access to any of these improved water sources.

Does it solve the drinking water crisis? No! Because drinking water has to be free from faecal and chemical contamination. A lot of the water supplied through piped networks by utilities (WASAs, City Corporations, and Municipalities) is not free from faecal and chemical contamination. The reason is poor treatment and supply networks. Similarly, a lot of borehole or tubewell water has faecal and chemical contamination problems, especially due to the presence of arsenic, iron, and salinity in the groundwater.

Poor faeces management contributes to it by polluting the shallow groundwater with faecal contaminants. Moreover, if water is not available on the premises or not accessible in the time of need, you have to collect the water from outside and store it. Poor storage can contaminate water from improved sources. According to JMP, water service can be considered ‘safely managed’ if ‘drinking water from an improved water source that is accessible on premises, available when needed and free from faecal and priority chemical contamination’.

If we consider this, only 58.8 percent of the Bangladeshi population has access to safely managed water services (JMP 2020). Only 15 percent of the population is under piped water supply – 2.9 percent of which are in the poorest quantile. Contamination of water is also of particular concern, with 86 percent of the poorest households showing E. coli contamination along with 16.7 percent of the population consuming arsenic water.

Despite a huge effort from the Government and Non-governmental Organizations (NGOs), progress is slow to achieve safely managed water services. There are many reasons behind it but the most critical reason is climate change. Floods, cyclones, earthquakes, and droughts are all common in Bangladesh, causing devastation to people’s lives. Safely managed water services that can reach everyone are extremely difficult – and climate change is exacerbating the problem.

Scientific forecasts have no good news for us. Satellite data show that annual rainfall rates in Bangladesh have fallen by about 10 percent over the past two decades, or by 10 millimeters per year (Water in Bangladesh: Rainfall). A study by Augusto Getirana and team on river-gauge data shows that the winter water flow of the Ganges, Brahmaputra, and Meghna rivers combined has halved between 1993 and 2021. This astounding decrease is likely to be a result of declining rainfall and increased groundwater pumping upstream in India for agriculture (Getirana et al 2022).

To tackle the situation different policy and practice-level changes are being taken. The following part of this article will capture a glimpse of the policy and practice level change for water service in Bangladesh.

Digbijoy Dey is a water and sanitation specialist currently working in IRCWASH Netherlands