Children from various ethnic minorities in hill communities were granted the right to learn in their mother tongues eight years ago, but progress has been minimal due to the absence of effective government initiatives and clear directives for implementation.

The initiative has struggled due to a lack of teacher training, no regular evaluation exams, mixed-ethnicity student populations in schools, exclusion from the official curriculum, and limited real-life application of the lessons.

Training teachers from these ethnic groups to properly deliver lessons should have been a priority, but this has not materialized.

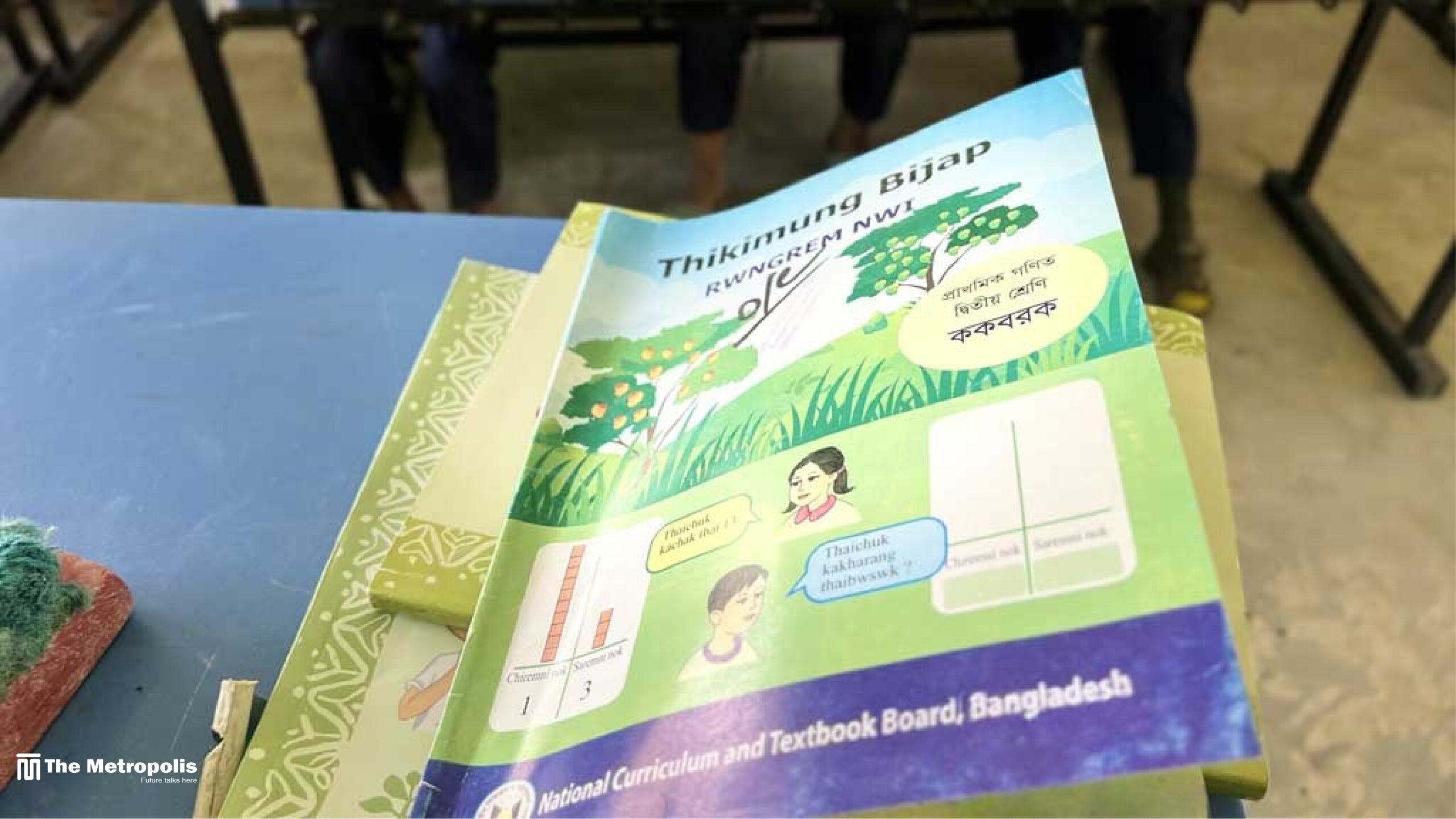

According to the Khagrachhari Primary Education Office, there are 595 primary schools in the district that have been receiving books in Chakma, Marma, and Tripura languages since 2017. However, the government only started training teachers five years after the books were first introduced.

In the 2022-23 fiscal year, only 90 teachers—30 each for Chakma, Tripura, and Marma—received institutional training to teach in their native languages. Beyond that, no further training has been provided.

Teachers question how the remaining 505 schools will manage without trained educators.

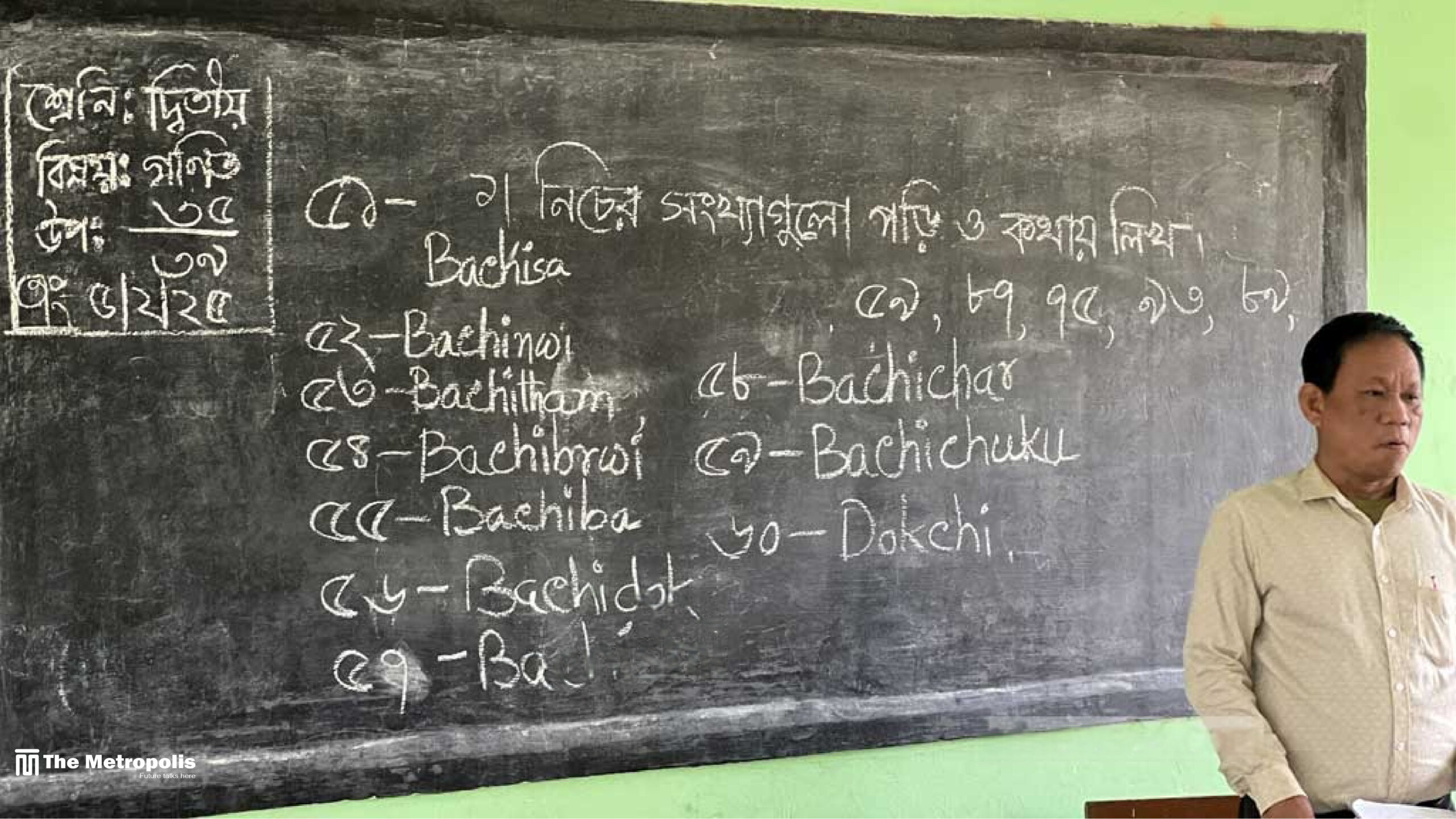

Chandra Kishore Tripura, an assistant teacher at Noymile Guchchhagram Govt Primary School in Dighinala Upazila, shared, “We’ve been teaching Kokborok [the language of the Tripura community], Chakma, and Marma languages since 2017. We received books annually but haven’t received any this year.”

He added, “No assessment system is in place. There are no guidelines on how or when to teach. We’re forced to teach based on our own knowledge, making it difficult for students to learn their mother tongues properly.”

The Directorate of Primary Education (DPE) reports that students from ethnic backgrounds are receiving books in five languages across 19 districts. A joint education cell within the DPE oversees the program in 16 districts, while Hill District Councils manage teacher appointments and other educational activities in three hill districts.

Rokhsana Parvin, assistant director of the unified education cell, stated, “District councils handle teacher training in the three hill districts. They can provide details on training ethnic minority language teachers. Training was recently conducted in one district, and programs are ongoing in two others.”

She added, “The NCTB [National Curriculum and Textbook Board] is developing a training module. Teacher training will commence once the PEDP-5 [fifth Primary Education Development Program] begins in the next fiscal year.”

Parvin acknowledged the challenges, saying, “It’s a complex issue. A teacher trained in one language may have students who speak four different languages.”

ONE TEACHER, MULTIPLE LANGUAGES

The 2011 Population & Housing Census reports that 1.1% of the country’s population, around 1.6 million people, belong to ethnic minorities. Many of them lack literacy, and numerous ethnic languages have no written form.

The International Mother Language Institute notes that 14 ethnic languages are endangered, though advocacy groups claim the number is higher.

To preserve these languages, the government introduced mother tongue education for pre-primary children in 2017, starting with books in Chakma, Marma, Tripura, Garo, and Sadri. However, no new languages have been added since then.

Approximately 40% of ethnic minorities live in the Chattogram hill regions, with others spread across Rajshahi, Sylhet, Mymensingh, and more. Outside Chattogram, ethnic language education remains rare.

Pratibha Tripura, an assistant teacher at Manikchhari Hedmyanpara Government Primary School, said, “We haven’t received mother language books yet this year, though we did in previous years. A major challenge is the lack of trained teachers.”

“Our school has Chakma and Tripura students, but no Marma students. I can teach Tripura because I am Tripura, but we don’t have a Chakma teacher, so those students miss out,” she explained.

She continued, “The NCTB curriculum doesn’t list ethnic languages as subjects or specify when to teach them. We teach stories and poems in mother tongues during free time.”

NO TESTS FOR ASSESSMENT

Teachers believe that the absence of assessments prevents students from taking mother language lessons seriously. Assessment tests are expected to be introduced this year.

Pratibha noted, “Students aren’t evaluated in their mother tongue, whether written or oral. If assessments existed, students and parents would be more motivated.”

Jaleswar Tripura, an assistant teacher at Noymile Guchchhagram Government Primary School, said, “We started teaching the Tripura language in 2017, but there were no official guidelines. Without evaluations, students lack motivation to learn.”

“The government supplies books but doesn’t provide trainers or assessments,” he added.

Md Shafiqul Islam, Khagrachhari District Primary Education Officer, offered hope: “We’ve distributed mother language books in Khagrachhari, but there’s no teacher training. I’ve spoken to authorities about arranging training.”

He continued, “The previous curriculum didn’t include exams, but the new one does. Teachers will now conduct assessments.”

HOW MUCH ARE CHILDREN LEARNING?

Prachurja Dewan, a sixth grader at Khagrachhari Government High School, recalled, “I got a mother language book in third grade, but it wasn’t taught well. I don’t remember anything now.”

His mother, Nipa Dewan, added, “Schools didn’t properly teach mother language books. There are no books for fourth and fifth grades, so children forget what they learned.”

Chaihlapru Marma and Kranuching Marma, also students, said they learned their mother tongue alphabets in Bihar and still remember them due to regular practice.

Nagui Tripura mentioned, “We had one mother tongue lesson a week. I can still write numbers in Kokborok.”

Parki Chakma, an assistant teacher at Khagrachhari Mahajanpara Government School, said, “I didn’t know the Chakma alphabet until a five-day training. I used to teach mother language twice a week, but the current routine doesn’t include it, so I stopped.”

IRE OF PARENTS

Parents expressed frustration over the lack of proper instruction.

Ganesh Tripura from Dighinala Upazila said, “Even though we have mother language books, they’re unused. Without assessments, students don’t take lessons seriously.”

Kabita Tripura echoed this sentiment.

Bikash Chakma from Khagrachhari District Sadar added, “Chakma has its own alphabet, but even Chakma teachers often don’t know it. Without proper training, they can’t teach the students.”

WHAT AUTHORITIES SAY

Samabesh Chakma, an education officer in Khagrachhari Sadar Upazila, shared, “We’ve instructed schools to teach mother languages once or twice a week, but the official routine doesn’t reflect this.”

He emphasized, “Teachers need training. Even Chakma teachers may not know the alphabet.”

Kanika Khisa, another district primary education officer, noted, “The NCTB’s routine doesn’t allocate time for mother language lessons, which complicates teaching.”

Shafiqul Islam concluded, “We’ve provided guidelines for 35-minute lessons per subject. We’ve requested regular teacher training in recent directorate meetings.”